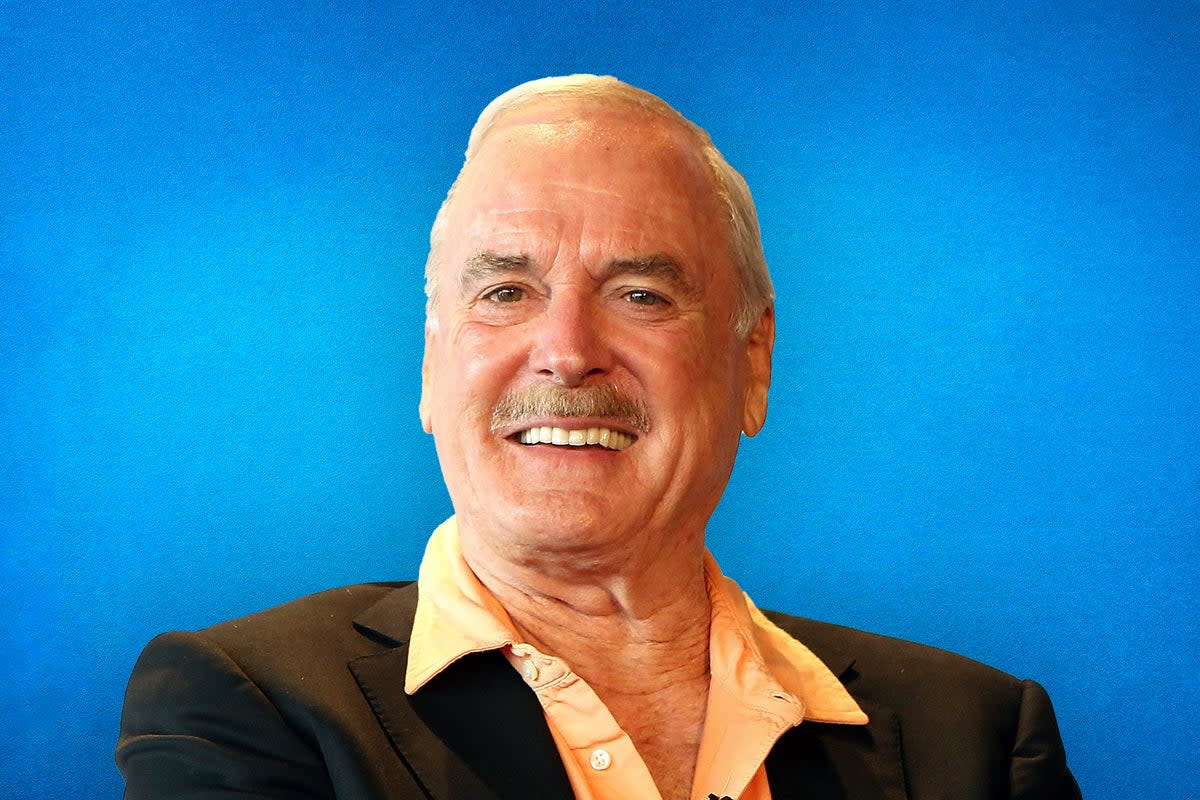

John Cleese is spending thousands on stem cell therapy – is it really the secret to anti-ageing?

John Cleese reckons he has found the secret to slowing down the clock – and it’ll set you back a mere £17,000 each year. The procedure in question is stem cell therapy, a treatment that the Monty Python star undergoes every 12 to 18 months. “These cells travel around the body and when they discover a place that needs repair, they’ll then change into the cells that you want for that repair, so they might become cartilage cells or liver cells,” he explained to Saga magazine. “So I think that’s why I don’t look bad for 84.” Of course, he specifies, only “the highest-quality stem cells” from Switzerland will do the job. He also told the magazine that he is “surprisingly poor” despite his long and successful comedy career, to which I can only sigh: John, being an advocate for Swiss stem cell treatment and claiming to be a bit hard up tend to be mutually exclusive activities.

Barely a week seems to go by without another celebrity extolling the virtues of some weird, wonderful and devastatingly expensive treatment or elixir that might guarantee them smooth skin and eternal youth (see also: Jennifer Aniston reportedly getting salmon sperm injected into her face, or the scary-sounding “vampire facial” favoured by Kim Kardashian, which involves having your own plasma applied back onto your micro-needled face). Yet this isn’t a flash-in-the-pan craze for Cleese: he’s apparently been undergoing stem cell therapy for around two decades, and believes that “buying yourself a few extra years” makes the cost “worth it”. And he’s not the only one. Last year, the US-based cardiologist Professor Dr Ernst von Schwarz claimed that Hollywood’s finest are regularly dropping thousands of dollars on stem cell facial injections. “They might or might not openly talk about it, some do, but it’s a lot [of celebrities],” he suggested.

So are stars like Cleese on the right track – or are they falling for a pricey fad? Stem cells are actually pretty remarkable. They are found in almost all of the body’s tissues, and “play essential roles in tissue maintenance and facilitating repair following injuries”, explains Dr Prashant Ruchaya, senior lecturer in physiology at the University of East London. They’re able to develop into specialised cells through a process called differentiation: they might become a blood cell, muscle cell or brain cell, and can help to fix parts of the body that have been damaged through wear and tear or affected by disease.

Some are much more versatile than others. Most flexible are embryonic stem cells, which come from embryos that are a few days old, as “they are used for the whole foetus’s development and must create everything that makes us human”, says Dr Gareth Nye, programme lead for medical science at Chester Medical School. These are the stem cells that tend to be used in research – their adult counterparts just aren’t as adaptable. But both types can replicate many, many times. This capacity for self-renewal makes them particularly intriguing for scientists exploring how the body fights illness: for example, Ruchaya’s recent research involved growing a cluster of heart cells with cardiovascular disease from stem cells, allowing scientists to better understand how this condition works.

Stem cell therapy has long been used to treat conditions from leukaemia to anaemia; there’s also research under way to see whether it can help with type 1 diabetes and Parkinson’s, Nye says. And athletes, including the likes of Kobe Bryant, Rafael Nadal and Cristiano Ronaldo, have reportedly undergone state-of-the-art stem cell treatments to help rebuild injured tissue, too.

Inevitably, there has been plenty of buzz about whether the cells’ regenerative properties could be harnessed to slow down or even turn back the ageing process. There are a few ways that this might potentially work, Ruchaya notes. Their ability to develop into different types of cells “could be harnessed to replace damaged or ageing cells in tissues or organs”, he explains, which “may help to restore function and vitality to ageing tissues and reverse age-related decline”. They also produce anti-inflammatory molecules, which could counteract lots of age-related diseases. “And finally”, he says, “stem cells release growth factors and other signalling molecules that can enhance neighbouring ageing cells to function more effectively.” One study has even found that stem cell treatment managed to reduce wrinkles… in mice.

But Nye says it’s crucial to remember that, right now, clinical research exploring stem cells’ impact on ageing is currently only in the testing stage: they certainly aren’t approved for that kind of use. Last year, researchers at the University of Reading and the Universiti Sains Malaysia called for stem cell treatments to be better regulated, after coming across hundreds of clinics around the world offering unproven “therapies” and products for various complaints. Plus, there’s a risk of contamination – and when you introduce cells that can divide into any cell type, cancer can be a concern too.

So the prospect of “buying a few extra years” using this therapy “remains speculative and requires further robust scientific evidence”, Ruchaya says. “It isn’t as straightforward as you think. You can’t just rely on stem therapy, you may need co-therapy [ie other treatments]. You also need to look at genetics.” Maybe put that trip to Switzerland on hold for now: your bank balance will certainly thank you.

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle