A documentary exploring the fascinating life of Diane von Furstenberg is out now

“I’ve never sat down and tried to plan out the future,” Diane von Furstenberg once told Harper’s Bazaar. It was the summer of 1976, and her signature wrap dress — a zip- and button-free creation that tied in the front like a robe and came in an array of vibrant prints — had captured the imagination of America, along with the woman who designed it. Von Furstenberg was the fiercely intelligent and glamorous Belgian-born daughter of two Holocaust survivors who had married a German prince (which made her a princess), become a mother of two, and relocated to New York, where she and her high-flying aristocratic husband took the Manhattan fashion, art, and society scenes by storm — all before her 30th birthday.

The dress, which retailed back then for $86, made Diane von Furstenberg a household name. In fact, von Furstenberg herself became so synonymous with that single item of clothing that she often wondered aloud if it would become her epitaph. (“It will probably be on my tombstone,” she once lamented. “‘Here Lies the Woman Who Designed the Wrap Dress.’”) But it would also serve as a lasting symbol of the almost voracious sense of style, ease, and self-possession with which von Furstenberg seemed to navigate the world — a subject very much at the centre of the new documentary Diane von Furstenberg: Woman in Charge, which premieres 25 June on Disney+.

As a designer and a businesswoman, von Furstenberg has always been shrewd — and even prescient — about the ways in which she has made her personal story a part of her brand. Directed by Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy and Trish Dalton, the documentary explores what it’s been like to actually live that story for its protagonist, now 77, who provides a guided tour through some of the more extravagant highs, sobering lows, and transformative moments.

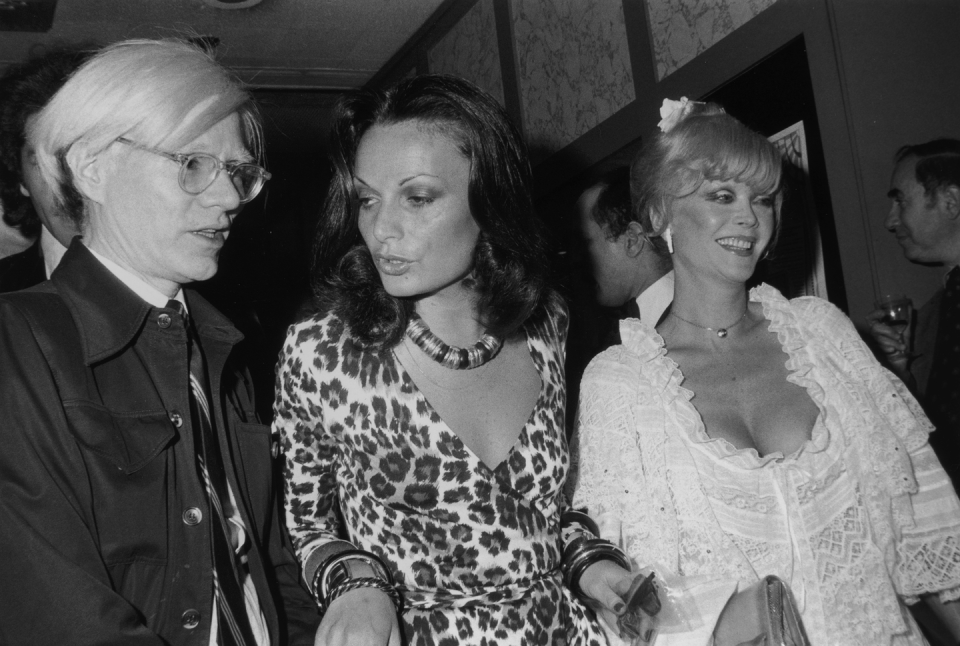

There is the enduring influence of von Furstenberg’s mother, Lily Nahmias, a survivor of the Nazi death camps at Auschwitz and Ravensbrück, who suffered such extraordinary physical and psychological abuse that she was told by a physician that she should not have children. There are the glittery and unvarnished aspects of her marriage, at the age of 22, to Prince Egon von Fürstenberg, which if not fully open was very clearly ajar, and the fallout from the different kinds of freedom they both embraced, which culminated in their divorce. There are her exploits during the Studio 54 era (Von Furstenberg would come home from work, put the kids to bed, and head out for the evening while Lily kept an eye on them). And there are her formative romances and excursions — with a female friend in boarding school; with an Italian writer in Paris; with a Brazilian named Paulo in Bali; with Warren Beatty and Ryan O'Neal in a single weekend.

The film delves into von Furstenberg’s close, and occasionally complex, relationships with her children, Alexander von Fürstenberg and Tatiana von Fürstenberg, and her current husband of more than two decades, Barry Diller, who are all interviewed alongside famous friends like Marc Jacobs, Fran Lebowitz, Gloria Steinem, Anderson Cooper, Hillary Clinton and Oprah Winfrey. Much of the narrative is also framed around her myriad business successes and challenges — the wrap dress’ periodic swings in and out of style, the overly ambitious expansions and withering contractions, the purposeful retrenchments and unlikely renaissances.

Overall, it’s a colourful rumination on both the woman von Furstenberg has always wanted to be (to paraphrase the title of one of her memoirs) and the woman she has become: as a partner, mother and grandmother, whose 25-year-old granddaughter, Talita von Fürstenberg, is now involved in her company; as a whispering angel of sorts to multiple generations of designers, most notably during her tenure from 2006 to 2019 as president of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA); and as an ardent supporter of other women through initiatives like the DVF Awards and her work with organisations like Vital Voices, which seek to promote women leaders, advocates and activists in a wide variety of arenas.

But for a subject who has always seemed to practice a kind of radical presence, it’s almost appropriate that some of the most powerful scenes in the film involve von Furstenberg not recounting the past but confronting it in real time as she returns to a school she once attended in Brussels; or searches for her mother’s image at a Holocaust memorial; or recalls Egon’s death from complications from AIDS in 2004; or reads aloud a not entirely flattering letter that Tatiana wrote to her as a child.

For Obaid-Chinoy — a two-time Oscar-winner for her documentaries Saving Face (2012) and A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness (2015), which each examined different forms of violence and injustice against women in her native Pakistan — the heart of the DVF story lies somewhere beyond the swirling tastes and tropes of fashion and in the ways we think about things like power and identity and understand our own potential and possibilities. (Obaid-Chinoy is now slated to direct an upcoming instalment in the Star Wars franchise.)

She, along with von Furstenberg, and one of the film’s producers and prime movers, Fabiola Beracasa Beckman — who previously co-produced 2016’s The First Monday in May, about the making of the Met Gala — recently came together to discuss Diane von Furstenberg: Woman in Charge, why fashion is never just about fashion, and what it means for forge a legacy.

FABIOLA BERACASA BECKMAN: About seven years ago, I put together this moonshot deck of stories I really wanted to tell, and DVF’s story was my crowning jewel. I had known DVF for a very long time, and she was a great source of inspiration to me, so it was a no-brainer as to why this movie needed to be made. So I asked her if we could do it in every which way imaginable. I was casual about it. I was formal about it. I was nice about it. I was firm about it. And DVF said no — nicely, firmly, in every which possible way as well. So, I had kind of resigned myself to the idea that we were never going to make this film.

DIANE VON FURSTENBERG: Well, I have a personal relationship with Fabiola. The father of my children was roommates with her father in boarding school, so I knew Fabiola before she was even born. Obviously, I wanted to please her, but I wasn’t ready to have a documentary made about me. And then because she is producing movies and I’m so involved with championing women and amazing stories of women through things like the DVF Awards and Vital Voices, I thought, “Oh, maybe we should make documentaries about these extraordinary women.” Then, of course, I thought of Sharmeen because she is also somebody I’ve known for many, many years. We actually met on-stage, when I was asked to present her with an award. It was a very moving thing because Sharmeen had done this incredible film called Saving Face, for which she had won an Oscar. It was about these women who had been attacked with acid. Anyhow, Fabiola and I had this idea to do these documentaries on these incredible women and then I kind of seduced Sharmeen into joining us. Sharmeen and I have the same agent, so we asked our agent to talk to different networks and people about making these films, but no one seemed very interested. But they kept on telling our agent, “We want a movie about her” — meaning me. And that’s when Sharmeen came up and said that she liked… Well, Sharmeen can speak for herself, but she is the one who eventually convinced me to do it.

SHARMEEN OBAID-CHINOY: I think the idea that did it for me was that we began having this conversation about how DVF has been able to chart her own life and really make decisions. If she’s fallen down, then she’s picked herself back up. She has always had this very strong sense of, “I know where I want to go. I want to be a free woman, and I will chart my own life.” As a filmmaker, I have worked around the world. I have been in war zones, in developing countries, on the front lines, and the message every woman has given me is that they would love to be in charge of their own life. So I thought that if one could tell DVF’s story and show that it is okay to own who you are, against all odds, that I would be able to use this film to inspire women to understand that it is okay to be true to yourself. That is why someone like me would be interested in telling this story. This film is not just a film. It’s a conversation about the things that one needs to do to protect oneself, that one needs to do to open up to the world. As I embark on this journey in Hollywood, there is so much I have learned from DVF and from interviewing other people that made me really understand that it’s okay to chart your own path. I think that’s what we really hope that women — and young girls especially — take inspiration from, certainly in a world now that’s so deeply divisive, where you find that so many young women no longer have agency over their lives.

FBB: I remember one day I was with DVF on Little Island, near her place in the Meatpacking District, and very much true to DVF form, after having said no for a thousand times, really in her own time, she came up to me and said, “You know what? I think I want to do this.” And I was like, “What? Okay!” I was so excited. But it was really on her own time, in her own way, when she felt she was ready.

DVF: Well, Sharmeen is a very strong woman. She is very strict. The minute I said, “Okay, you guys can make this movie,” I could no longer be a producer, obviously. I had to pull myself out of it completely and just be the subject. So I became the subject and the subject only. I made absolutely no decisions about the film. I don’t think that Sharmeen would have let me because she is a very forceful director. She wants to do it her way. I had to respect that — and actually, it’s kind of nice to be only the subject. I was a very cooperative subject. I have an enormous amount of footage because I keep everything, so I had my mother on tape and movies from my childhood that we got from my brother. So I was cooperative in that aspect of things. But it was really your movie. Even the title — I had absolutely no decision-making on that at all. And then once you had the title, I didn’t even want to see the movie, because I liked the idea that I could go to the opening and tell people I hadn’t seen it. But Sharmeen insisted upon me seeing it. So that was that.

SOC: How was that?

DVF: How did it feel to watch it? Well, it felt like I was at the gynecologist for an hour and a half. I mostly laughed. But laughing for me doesn’t mean that I’m having a good time. It’s my defence system, I recently realised. And then, of course, two days later I got panicked. I’m still panicked. But at this point, the film is out there, and I hope it will inspire other people because Sharmeen convinced me to do this when she said, “I want girls in school in Africa to see this movie and for it to give them strength.” But it is very weird because I have used my life, I have used my family, I have used every one of my experiences, and I open up always — not just in this movie, but in general. And then sometimes I just think to myself, what kind of a life is this? Why do I expose these things? But I guess it’s just my destiny. I am using the experience of my life to kind of... I don’t know.

SOC: But this film is also fun. You’re also learning about this incredible woman who was born on one continent and ended up on another continent, the journey from one to the other, the life that she has led, the creation of a single garment that literally changed the world and empowered women to dress a certain way, the confidence it brought to them. And that era that we are talking about — it’s unfathomable to young people today to think about America in the 1970s. That decade was such a special decade, when things seemed to be opening up for women, and it comes alive in our film. This film is not just about Diane. This film is about World War II. It’s about Europe in the 1950s. It’s about America in the 1970s. It’s about the 1980s. It’s about the business downfalls that took place and then the rebirths. And with each of these steps in your life, we introduce the world that surrounds you. We’re making this journey with you but also reliving these big moments that shook the world in so many ways, whether culturally or socially or politically.

FBB: That’s why for young girls to see a woman who is such a disruptor, such a trailblazer, be unapologetically herself — to really have that beacon as an example — is so important today. I really believe that you have to see it to be it and when we don’t see ourselves in others, we don’t believe things are possible.

DVF: The most audacious thing I did was being born. I wasn’t supposed to be born. My birth was a miracle. So I started out with a bang, and anything else after that was a plus. Yes, I married a prince. Yes, I did this, and I did that. But very early in my life, I realised that the truth is so important, even when the truth is not so pleasant, and that sharing a difficult experience instead of hiding it and making it look better… It’s better to just own it without complaining, without blaming, and move on. Now, I’m an older woman. I’m definitely in the winter of my life. And if I can share my experience, my knowledge, my connections, and all the things that I have to help others, then great.

SOC: We also find ourselves and the world at a place right now where there are difficult conversations taking place. Here we have a Jewish woman, who was the child of Holocaust survivors, and you have a Muslim director, who is directing the film about her life. I really think that is such an important message — about a joint conversation, and how we go back and forth in that conversation, that we are essentially all the same. Bringing this piece of history to the screen and bringing my own experience as a Muslim woman to it and some of the shared experiences that Diane and I have had — it’s so important for the world to see that right now. Again, I think the message of the film goes beyond Diane’s life. It’s really about bringing voices together.

DVF: It’s focusing on our similarities as opposed to what separates us. Also, what happened with the making of this movie, is the relationship amongst all of us. We spoke daily. In the middle of all of this, Sharmeen was hired to direct the next Star Wars movie — a Muslim woman is going to direct Star Wars. So there was that adventure that she was going through, which obviously involved jumping into a very different, very male-oriented dynamic. She would interview somebody about me and then she would call me and say, “You know, by doing all these interviews, I’m learning so much about things I need to know now.” So that made me feel really good about doing this movie because if Sharmeen, who is a tough one, felt that way, then that meant that maybe it could be meaningful to other people.

FBB: As a mother of three young children — two boys and a girl — I think one of the things I learned in this process so deeply from DVF is just that fear is just not an option. It’s one of DVF’s favourite things to say, and I used to hear her say it and not quite understand it. But as I spent so much time with her, I started to understand what she meant. It’s about this way of adapting. She has this adaptability that allows her to move through the world without fear because she always knows that there’s another way to go about or react to something — that fear is not the only way. After I saw how she was able to live that in her own life — and how well it served me once I started applying it — I felt the need to teach it to my children.

SOC: When we took Diane to Brussels, I also saw a side of her that I had not seen before. When she was growing up in Brussels, she said she felt like an outsider because she had this dark curly hair and everyone in her school was blonde and blue-eyed.

DVF: I was the most ethnic-looking person in my school, for sure.

SOC: And then I began to think about the concept of the insider and the outsider, and how one would never imagine that Diane ever felt like she was not welcomed or that she felt different in a place. Yet as we walked the streets of Brussels, she talked about how, when she was younger, she could not wait to get away from there. Of course, Diane made her life in America, but when she came back, it was like she was reclaiming part of herself. When we went back to the school it was like this big circle moment, Diane, because everyone in the audience now looks so much more like you. The blonde and the blue-eyed are now a minority, and the dynamics of the school had changed so greatly. We felt like it was a full circle to go back there.

DVF: There’s so much also that is not in the movie, obviously, because there is limited timing, but at some point, Sharmeen made me talk about my experience with cancer. I had cancer 30 years ago, so I was telling my story, talking about the way I felt, and then I said, “I wonder how I actually wrote about it when I was diagnosed.” So I went downstairs and pulled out my diary from back then and read it. I was curious to see. And I was actually happy with the way I wrote about it, with a detachment, which is always something I talk about — that when you go through a difficult moment, you push the emotion away, push the fear away, and just deal with it. So I was happy with how I wrote about it, and happy with myself, inside myself, reading that.

FBB: I love telling fashion stories because they have this “Trojan horse” quality. You don’t always think that they’re going to explore particularly deep or intellectual topics, but in fact, fashion stories provide a lens to explore so many facets of humanity.

SOC: Telling stories that surprise people, that move people, that push them to see the world in a different way, that push them to walk in other people’s shoes — I think with each one of these projects I do, that is at the heart of it. That’s why with this film, even though everyone looks at Diane as this fashion designer who trapezes through the best of Europe and the best of North America, I see Diane as a woman who has been true to herself, who has fought sexism, who has fought a male-dominated industry, who has, as I said, fallen down and picked herself up. I see that at the heart of the story. When I began to look at the archives and saw the early interviews Diane did, where she was sitting in front of some very, very famous people and seeing the questions that were thrown at her, I started to think about how every working woman goes through that: whether it’s the kinds of questions that are thrown at her in a boardroom or when she’s looking to get a job that she deserves or when she’s trying to introduce a concept that the world has not seen. Because it’s a woman, then somehow there is some sexism that comes with that. And that’s what I want the world to also see: that it’s never easy; that you have to push open the doors that are closed for you. When people watch this film — especially people who see Diane in a very different light today — I want them to be able to connect with her struggles and realise that there were real moments in her life when she had her back against the wall and found a way forward, that she made a path for herself despite everything that has been thrown at her.

DVF: As a young girl, I don’t think kindness was my first trait. When I first started, I think I was much more interested in being independent, in being in charge — and I became in charge through designing a little dress, and blah, blah, blah. But I’ve discovered over the years that kindness is actually a kind of currency. It was an amazing discovery. So what does it mean then to be in charge? It’s not an aggressive statement. It’s about making a commitment to yourself. It’s about owning who you are. You own your imperfections and they become your assets. You own your vulnerabilities and turn them into strengths. It’s always about being true to yourself, because if you’re true to yourself, then you are free. You can’t decide a lot in this life. You can’t decide who your parents are. You can’t decide where you are born. You can’t decide anything about the collective madness around us or the things that surround you. You are not master of your destiny. But what you are master of is how you navigate your destiny. And once you have somehow found a way to navigate your own life, then sharing and paying attention to others becomes an entirely new universe to explore. I like to play this little game every day. I try do at least one miracle a day by introducing someone to someone else they would’ve never had the opportunity to meet otherwise. I do that all the time. It’s funny because sometimes I go through so much work to make those things happen, but that’s the new part of my life and it is really nice. To help people and to connect people and to expand people’s worlds—that’s really when you have a sense of the power that you have.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle