My Whole Life, I Embraced My Latina Identity. Then I Took A DNA Test That Changed Everything.

Friday morning began in the Los Angeles International Airport. I was preparing to board my flight to go visit my father in Seattle. This would also be the first time that my partner of three years would meet my dad. I was nervous and excited, but both feelings would be replaced by something entirely different just moments later.

I heard a chime on my phone and looked down to see an email from Ancestry.com. My fingers flew to open the email. I had been waiting two painfully long months for the results of my DNA test. While on my mother’s side I knew I was thoroughly European, I felt there was something missing from my paternal genealogy. I had been waiting for this test only a few months, but this was a mystery I’d wanted to solve my whole life.

As with many families in the Southern U.S. with ancestry originating in the slave trade, I was eager to see where my ancestors had migrated from on the West Coast of Africa. While there were many unknowns that I was eager to uncover through my DNA, one thing I was certain of; I was Puerto Rican. My name was Cuba Jimenez, after all.

I opened my results right as pre-boarding was called, scanning the percentage breakdowns below the multicolored world map. Cameroonian. Congolese. A lot more than I was expecting of them. British. Scottish. A lot more of that, too. My partner was the first to call it out. “There’s no Spanish. No Taino.”

I didn’t realize what she was saying. I checked the map again. None of those fun little migratory circles even touched Spain or the Caribbean.

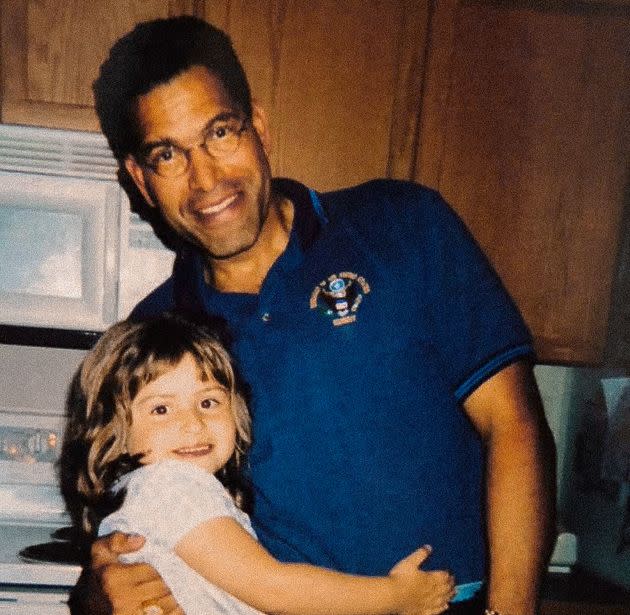

I had my grandfather’s birth certificate. There was no doubt that Luis Jimenez-Cruz was born in Arecibo, Puerto Rico. A military man who was assassinated in Panama during the Martyr’s Day riots and buried in Arlington cemetery. His records were everywhere. My father’s were not. Then and there it clicked that Luis couldn’t be my grandfather. I triple-checked to make sure my father’s maternal ancestry was in line with my own. Yes. My dad was my dad, but my grandfather was not.

Perhaps it wouldn’t have been a big deal for some. These kinds of secrets could be found in everyone’s family tree. There are stories all over TikTok of people uncovering secret lineages and ethnicities they’d never known about through DNA testing. I searched Reddit stories on the plane and found many that echoed my own.

In my own life, I’d known a woman who’d uncovered a secret brother through a DNA analysis site. According to the Pew Research Center, 27% of American adults who took mail-in DNA tests reported being surprised by a close relative result.

Yet, my story meant that my name, Cuba Jimenez, wasn’t truly mine as I wasn’t a Jimenez or Latino at all. My identity was wrapped up in years of sailing in Florida and the Caribbean. In pernil and conch and coconuts. It was marked by the struggle of trying to learn Spanish and being criticized for my accent. Hell, I was a Latino Media major in college. I had never claimed to solely be Latino, but it was certainly an extremely proud part of my mixed heritage. I suddenly felt the urge to rid myself of the name as quickly as I could.

“I’m finding a new last name,” I told my partner as our boarding group was called. A part of me felt deceitful, though never intentionally, for having worn Jimenez for so long when it wasn’t mine to use. I sat on that plane for two hours and cried. I was having an identity crisis at 30,000 feet.

I loved my Puerto Rican heritage. The stories of my dad’s time as a child in PR were a part of me and I cherished them. It was important to both of us, I knew. He as much as I loved where his dad had come from. He had continued to visit and live in the Caribbean long after my grandfather was gone. I had never known any of my grandfathers, so this name and my dad’s stories were all I had.

Although there are large Black communities on the Caribbean islands, Luis was a white man. The man whose DNA had shown up on my chart came from early African Americans brought to the southern United States by the slave trade. So my dad had two Black parents, not one. I pondered on what this meant for me. Being a mix of Black and white wasn’t hard for me to accept, as it was already a known element of who I was. But giving up a separate part of my identity felt like a tremendous loss. I also didn’t know the circumstances surrounding any of what I had discovered, and that scared me too.

When I saw my dad it was all we could talk about. I had texted him the information on the plane and I know we both spent the following 24 hours with our heads spinning. We felt different, somehow, but we didn’t know what had changed.

I reminded him and myself that Luis didn’t share our DNA, but he had been a willing and loving father every day until his death. That made him our family. My dad had learned his food, music, and everything about who he was from his Puerto Rican stepfather. That made it his culture, too.

The DNA linkages didn’t lead me very far, anyhow. A monumental bomb had been dropped on my life, and when the dust settled, there was nothing there. A few anonymous matches to second or third cousins. No real answers for the now increasingly long list of questions I had.

I began to think about my mother’s family tree. Mostly British, and entirely filled with historical records and documents dating to the 1400s. Genealogy was a fun brain game for those with European ancestry, finding histories that told them what their 9th great-grandparents were doing in the Georgian era. For nearly everyone else, it was a painful awakening to lost stories, erased histories and generations of trauma.

There is a documented difference in surprise DNA results for Americans of color versus white Americans. According to Pew Research, only 22% of white mail-in DNA test takers were surprised by results concerning their ethnic or racial background. In contrast, 42% of nonwhite Americans reported surprise at ethnic ancestry findings. Just like the DNA I had anticipated versus that which had stunned me, it seemed to be a pretty black-and-white issue. Knowing your ancestry is its own kind of privilege.

I thought back to what I had heard an Indigenous friend say about blood quantum being a colonizer ideology. I wondered if the same could be applied to all forms of DNA percentage tests. Now, with the acknowledgement that I am half white, there is no pretending I will ever divorce completely from whiteness. But the idea that blood makes us who we are, that was something I could leave behind in shedding a Eurocentric view of the world and of myself.

I, like everyone in the world around me, was shaped by every aspect of my environment. By the people that I know and will come to know in my life. By the neighborhood I grew up in and the teachers I’ve had. In part, I am also shaped by the blood I share with those who came before me, but that is just one important aspect of who I am. As Vice President Kamala Harris said, I didn’t just fall out of a coconut tree. There is a ton of context.

So perhaps Jimenez is exactly who I am. Perhaps the whole thing is a part of my story and my identity is made up of every part of it. I can open myself up to learning about new connections and what my ethnic makeup means. I can still struggle through my Spanish and enjoy the Puerto Rican recipes I love. I may not be a Latina, but I am a Jimenez today and always.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch at pitch@huffpost.com.

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle