I Had An Ominous Fear About My Husband That I Kept Secret For Years. Then It Came True.

The author and Simon on their wedding day, May 6, 2012, in Kent, U.K.

Simon and I couldn’t be more different. When we met, I was 38, he was 54, and his unabashed zest for life broke through my complicated caution. I knew I was in love when, after a lazy summer evening together, I lay on the stone beside a Trafalgar Square fountain and felt joy seep through my skin.

I moved in with him, his rural 15th-century cottage becoming our home, workplace (me in medicine, he in shipping), and where I discovered previously unknown contentment.

After a decade, as others might contemplate retirement, Simon decided to retrain as a boatbuilder. We relocated to a stunning coastal town. He studied and then created a business with fellow graduates.

Fitter, stronger, tanned, with resin in his hair and a pencil behind his ear — and already so good at being happy — Simon said he’d never known anything like this new life of ours.

Me too, except for the shadow: While loving him, I lived with the constant dread of losing him.

This wasn’t entirely new.

Simon (second from left) in his workshop in 2018 with a boat he built and his (slightly) younger colleagues, Shep (far left), Jamie (second from right) and Sam.

A parental war-zone childhood made me fear for my wonderful, careworn mother. I learned that good goes bad. Night always follows day.

When I was 7, I figured the best way to protect against 24-hour cycles of pain was not to trust — if I let my guard down, hell broke loose.

Sometimes, I forced myself to imagine my mother dying: Things were manageable if they weren’t terminal.

I lived with this exhausting logic until I was 30, when good changes in my life shifted my focus, and I worried less about mum. But cancer soon shattered this truce and she died at 62.

Worrying about her hadn’t kept her safe, so it was pointless. Or ... had worrying less allowed her to die?

Having found Simon’s all-embracing love, I was taking no chances with losing him too. Ashamed of my unnatural fear, I told one friend about my relentless worrying and she became the voice of reason when Simon was late getting home or not answering his phone. I needed her incredulity: This was my problem to quell, not Simon’s to survive.

I remember telling him, “I can’t believe, with you, one lovely day can follow another.”

It was true — and new. I had glimpses of believing I could disentangle loss from love, but only glimpses.

Our shiny life together and my fear were so at odds, I mostly kept how I felt hidden. I didn’t want to oxygenate my anxiety with words. Simon knew its essence, but not its magnitude. How could I burden him with feeling I doubted his competence? He’d managed fine without me for decades.

If we spoke of it, he’d hug me, ask me not to mollycoddle him, and joke about my being scared when he went to the mailbox across from our house.

But I was.

Simon relaxing in the home office with Softie, our cat, in 2015.

I’d go into the bathroom of our home office, turn the light on, and start the noisy fan so I’d miss the screech of tires and the impact that I was terrified was coming. Then I’d hear him stroll back in.

He once said, smiling, that he thought I’d like him best wrapped in cotton wool and kept in a drawer.

In my defense (thin, but true), Simon had a terrible cardiac record and had been in some strange accidents. Our only skiing holiday ended after two hours, when we found ourselves in the hospital, where I tried to erase the vision of him heaped in snow and wrapped around a wooden post, blood trickling from his forehead. A complex shoulder operation followed.

Soon after, he fell backward while playing tennis. He suffered three breaks in his wrist and we spent the night in the emergency room before he underwent surgery.

Such events, interspersed with “routine” procedures on his arteries and his knees, oddly strengthened my resolve to stop worrying. He always survived, and was showing me, beautifully, how to live.

When the pandemic began, Simon suggested I keep a diary.

April 2020, he’s safe and the world is at a standstill. By June, he’s breathless. The last entry, from July, is a promise to myself: Once he’s OK, I’ll get help. Psychiatrist, therapy, whatever, to shift the fear he’ll die, so I can fully enjoy our life.

He was diagnosed in July with “stage 4 lung cancer in a non-smoker.” When we were told 25% of people with this diagnosis and the suggested treatment “do well after six years,” I was inexplicably sure he’d be among them. Seeing his confident smile in a photo taken on my birthday that year, as he held his favorite ice cream following his only treatment, now shreds my heart.

Simon enjoying his favorite ice cream in August 2020, after the only treatment he'd ever receive for his cancer.

Steroids for the side effects he experienced after that one treatment elicited psychosis. As that eased, he had a stroke.

Through 10 weeks in the hospital, nine weeks at home, and a week in a hospice facility, Simon put all the strength his broken body and fractured mind could muster into being himself.

During that time he insisted on wearing his favorite pink linen shirt for his palliative nurse’s visits. He encouraged, with amusement, a complicated ramp construction that allowed his wheelchair into the garden so he could watch the sunset. He never admitted the futility of exercises his physical therapist said might help him walk again. He ate pureed food (sometimes cooked just for him at his favorite restaurant even though it had been closed by COVID), fed by me, from a teaspoon. And he firmly said, as we arrived at the hospice, even though he was barely speaking by then, “This is a good place to be when you’re not feeling well.” I’m certain he wanted to reassure me it was right to move him, even though he had to leave behind his beloved cat, garden and view. A few days later, he asked for whisky — it was his last breakfast.

Simon died on March 3, 2021. He was 71 years old.

The undertaker let me put a cookie in Simon’s pocket before the funeral because he’d often told me he’d been scared since childhood about who’d feed him in his grave.

But did I fail him otherwise?

I stopped worrying and my mum died. Was this the same?

Simon’s relatives had heart disease and assorted medical emergencies but never cancer. I’d blithely disregarded what was racing through him while I made commitments in my diary to worry less.

Tiny lapses in my arsenal of fear, with mum, with Simon, and those I love disappear.

Simon on his beloved boat in his favorite place on the Turkish coast in 2019.

Floundering in the slipstream of our life together, I’ve joined grief communities, forums and online meetings.

Connecting with others felt good, but I was still searching for someone like me — someone who had experienced the apparently irrational fear of losing their beloved, only to be left grieving in its wake.

I turned to the bestselling Grief Works by therapist Julia Samuel, in which she writes, of losing a partner, “One of the most painful aspects … is having to parent alone.” This drove home the complex wound of childlessness alongside an obligation to accept my fortune — that I had been spared this particular facet of loss. And then she plumbed my shame: “When couples commit, death is rarely something they envisage, certainly not until old age.”

Boom.

There I was, on a dank March evening three years after Simon died, being told I won’t have anticipated this.

Experts concede each experience of grief is unique, but describe well-trodden healing paths. I felt increasingly isolated — no one talked about the grief that follows being so terrified your beloved will die that when it happens, you bounce between agony of their oblivion and shame at having rehearsed it — mentally straddling worlds with, and without — them while they were showering or making breakfast.

“Anticipatory grief” sounded accurate, but that’s for those dying, not foreboding for people as alive as Simon during the years when sweat trickled down my back just from hearing a siren.

I discounted “exaggerated grief.” It made me laugh, as I could hear Simon challenging: “How could grief for me be enough, let alone exaggerated?”

Maybe “complex grief”? But no, an article subtitled “grief gone awry” stated, “We naturally resist thinking of our own death and even more so that of our loved ones.”

Simon having tea at the edge of our garden in 2018.

And then I found a piece by Liz Jensen in the Guardian in which she wrote, “I was haunted by the terror that one day a child of mine would die. … Superstitiously terrified that if I told anyone, it might come true, I kept it secret. But it was killing me.”

In my muddle of loss, I finally felt seen as her tragic words chimed with my thoughts.

Could I have saved Simon by worrying better or harder or smarter? Did I somehow know he’d die an untimely death? I doubt both.

One friend, finding middle ground, said, “I know you knew ... I just hoped you were wrong.”

I have no idea how life would have felt, then or now, if I‘d not braced myself for this. Given our time again, I hope I’d live it without such turmoil. But it’s part of me, and despite it, I was loved by an exceptional man.

Occasionally I feel myself sliding toward fear for loved ones — even for Simon, forgetting he’s gone, or hoping he’s safe wherever he is. But mostly, such unease is stilled now.

Without him, I feel tethered to the earth by the thinnest thread, viscerally sure of what doesn’t matter — almost all the preoccupations that backdrop our lives — and what does: love, love, love, kindness, open-heartedness, open-mindedness.

I have a to-do list, tatty now, that I wrote when he died, scared I might not know how to keep on going or that I might even forget how to breath: find cat; ring someone; bake; swim.

The author and Simon in their garden during lockdown in April 2020, just before he got sick.

I can feel happy — it’s striking and it usually happens when I’m doing “something Simon.” Not just “his” jobs that no one shares now, or mending things in his shed, but when I catch myself thinking or behaving like him. He makes me a nicer person — and a better carpenter.

But beyond these moments, I don’t know what’s meant by “do enjoyable things,” so I work and exercise because both deplete my sadness of its fuel.

I regret judging others who’ve spun like dervishes after loss. Perpetual motion isn’t a sign you’re fine — keeping going just keeps you going.

I long to be invisible, except when needing company. I yearn for sleep, and dread hearing — and rarely answer — “How are you?”

Any reply feels too complicated. But it must be hard to imagine how I feel if I won’t tell you, so I’m glad I didn’t rebuke the friend who listened, puzzled, while I explained how Simon is everywhere, then peered at me and said, “But you do know he’s died?”

I do. But I also know that alongside his absence runs, at the best times, his presence far beyond memories. He’s in each molecule and breath, every ripple, wave and cloud. I survive because I have him, not despite losing him.

Part of my work is promoting better access to the sort of holistic hospice care he had, which means encouraging thought and talk of death, integrated with life. Not obsessively as I did, but in ways that support the dying and those left behind.

I’m left behind in a place so beautiful it hurts. Simon can’t feel today’s sun on his face — my sadness at that leaves me able to see beauty, but no longer feel it. It’s like taking a deep breath, but being unable to fill my lungs.

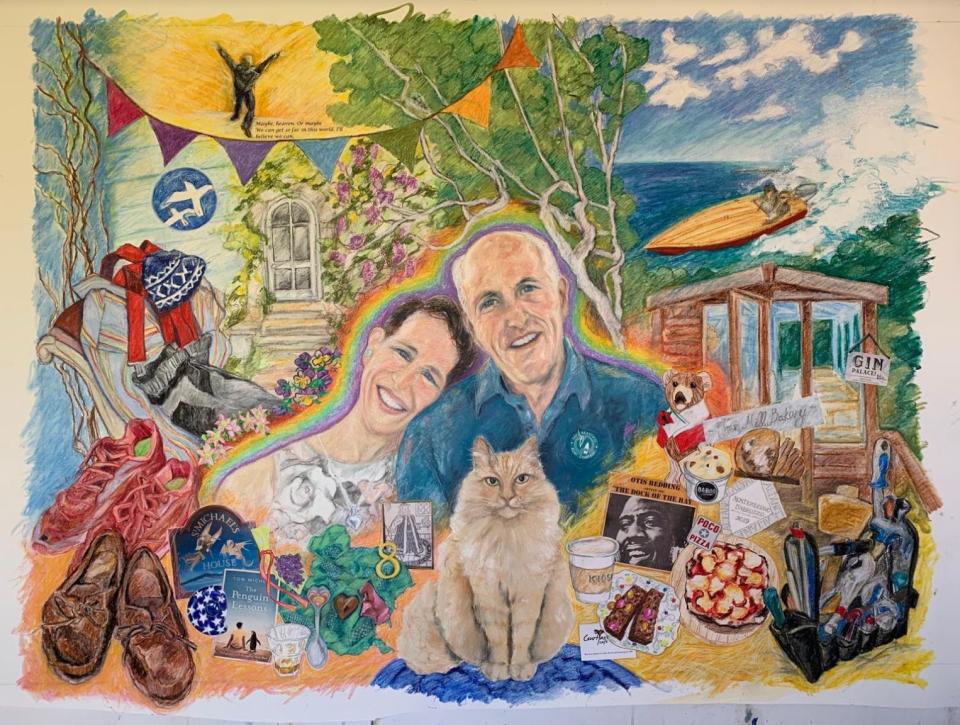

A mixed media creation (1x1.4m), including Simon's ashes, the author's and their cat’s hair. "A gift from a friend" the author writes. "It's like having Simon home."

I’m not the person I was before Simon. I have strength built on his love, and a new bit of me, carved by him, with capacity for joy. Maybe my life now is the pale price for such formative love, or perhaps I’ll find it again. I couldn’t have conjured up Simon, so all bets are off.

I’m writing this not so you can read about me, but in case you’ll read about you. And while I’m nervous revealing it, Simon would say, if our story lights someone’s darkness, then tell it.

Sophie Olszowski is a medical writer and journalist who has held senior roles in U.K. health care, written two books — “Doctor, What’s Wrong? Making the NHS human again” (Routledge) and “How to be an Even Better Chair” (Pearson) — and won awards for short fiction. She is now working to encourage greater openness about death and grief and improve understanding of what makes good end-of-life care and ensure access for all who need it. More at spzassociates.co.uk.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle