Fragile Beauty: Photographs from the Sir Elton John and David Furnish Collection, V&A review – Elegance, mystique and immense power

It’s only eight years since the last major London museum show of photographs from Sir Elton John and David Furnish’s collection. Yet such is the scale of the couple’s holdings and the speed of their collecting they could probably have mounted 10 exhibitions over that period without repeating a single work.

Tate Modern’s 2016 show The Radical Eye focused on Sir Elton’s first photographic love, classic early modernist photography, often severely abstract and almost exclusively in black and white – a taste that might seem surprising in so flamboyant a figure. The far larger Fragile Beauty takes us into the succeeding era, from the post-war period to date, with the couple’s personal preoccupations explored through iconic images by some of the world’s greatest photographers. Themes include fashion, celebrity, desire as represented by the male body, and the idea, suggested in the show’s title, of beauty as something vulnerable, even inherently tragic. Indeed, judging by the advance images, anyone who felt short-changed by the Tate show’s lack of high-style glitz and rampant homoeroticism will be in seventh heaven here.

Yet the first section – one might almost call them chapters – on “Fashion” shows how much photography owes to the modernist pioneers seen in the Tate show, and how much Elton has learned about the medium’s abstract underpinnings by studying them. Irving Penn’s Harlequin Dress (1950) with its peerlessly elegant composition of black and white checked dress, evening gloves and hat – worn by a peerlessly elegant model – brings to mind the bold geometric patterns of so-called hard-edge abstract painting. Norman Parkinson’s Cardin Hat over Paris (1960) in which the model is framed in the cockpit of a helicopter soaring over the Eiffel Tower has that sense of bravura anything-is-possible modern style it seems impossible to achieve today no matter how large the format or how expensive the equipment. Tina Barney’s spectacular, high-gloss The Limo (2006), is a case in point. Showing a model styled to resemble the iconic designer Halston in the back seat of a car beside a black man clad only in an expensive designer jacket, it’s immediately arresting, though its points about the interaction of identities and who’s looking at who, feel slightly too easy.

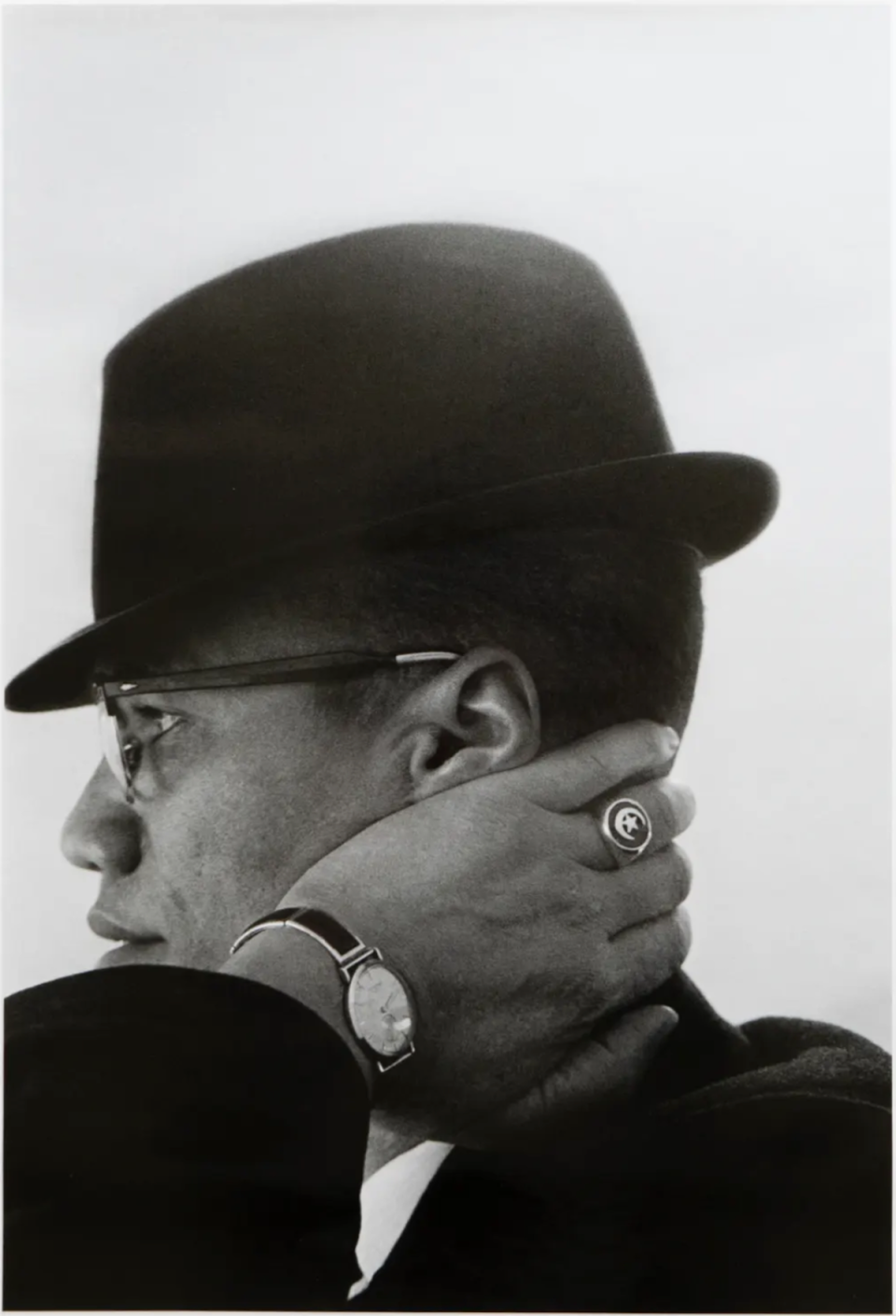

Given that Elton has lived for decades with the consequences of celebrity, it’s hardly surprising that “Stars of Stage, Screen and Studio” should be a theme here. The tragic destinies of two artists who obsess him, Marilyn Monroe and the doomed jazz trumpeter Chet Baker – both seen in superb photographs – embody not only his concept of fragile beauty, but the kind of fame-related disasters that could all too easily have befallen him. At the same time, we can sense his open-mouthed awe at being able to acquire seminal images of figures who have for him – and for many others – a near-religious mystique. We’re shown Sinatra with his Mafiosi minders in Frank Sinatra on the Boardwalk, Miami, 1968 by Terry O’Neill; Miles Davis, represented by three images of his very shiny hands, by Irving Penn; Bruce Davidson’s wonderful image The Supremes Preparing for a Show at the Apollo Theatre (1965).

Perhaps most telling are Richard Avedon’s amazing portraits of The Beatles, taken on 11 August 1967, at the summit of their celebrity, looking back at us with expressions that are at once wide-eyed and friendly and resolutely enigmatic. Their personalities have been shaped by an experience of fame that only they could ever fully comprehend.

The images of “Desire” feel more obvious, simply because the exclusively male subjects, from Gilbert & George in oversized underpants to Robert Mapplethorpe naked in the bath, are all so cheerfully “in on” the creation of the images. The only picture with the sense of risk necessary to a truly great photograph is Walter Pfeiffer’s Untitled (1984) in which five well-muscled young men look back at the camera with subtly varied expressions of confusion and hostility. No one, least of all the snapper, seems to know quite what’s going on.

But the most powerful section is “Reportage”, looking at the subject of “photojournalism”, which takes us to world-changing moments with an intensity that utterly transcends that rather bland term. We’re right up close with Martin Luther King, chuckling with his wife Coretta Scott King, captured by Stephen Somerstein at the end of the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965. We look on at the moment of stunned confusion immediately after the shooting of Robert Kennedy, snapped by Boris Yaro, in 1968.

Best of all are eight large, intensely dramatic, but unrelated images, all recent, any one of which has the capacity to reduce us to jelly, placed together on a single wall: from a ragged stars and stripes being carried upside down through a riot-torn American city in 2020 to Ukrainian women being waved off on a train and a dust-covered woman emerging from the bombardment of a Syrian city. While no specific point or narrative emerges, it’s clear that documentary photography – in the classic sense of going to a conflict zone and pressing the shutter – still has the capacity to yield images of immense power.

Yet in the section devoted to “Fragile Beauty” as a subject in its own right, the focus shifts from the intense scrutiny of the external subject to the subject performing their predicaments for the camera. An entire room is covered from floor to ceiling with Nan Goldin’s brutally raw images of marginalised 1980s New Yorkers, sprawled around their squalid rooms and acting up at bohemian parties. After the real-life horrors of the previous rooms, the allure of their self-advertising micro-dramas soon wears thin.

In the final stages of the exhibition, including an extensive section on “Constructed Images”, the emphasis shifts from the subject to the manipulation of the medium, whether it’s Andreas Gursky’s wall-filling digitally doctored images of North Korean rallies or Back to Black director Sam Taylor-Johnson’s faux-candid studies of famous actors crying for the camera. While it provides a visually compelling showcase for where art photography is now, it all feels a shade thin after the first half of the show’s brilliant exposition of photography as the ultimate observational tool.

Photography’s original promise was to give us chunks of physical reality with a veracity and level of detail that had never been seen before. Over the second century of the medium’s existence, we’ve become so preoccupied with the ease with which photography can be manipulated, with the fact that the camera actually does lie at every turn, that we’ve almost lost sight of that original power. The best images in this tumultuous show, from whichever period, have the capacity to make us excited about the very idea of photography, all over again.

At the V&A, from 18 May to 5 January

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle