New wild swimming spots won’t make our rivers and waters any less disgusting

As a middle-class woman in her thirties, I’ve had no choice but to fully embrace one cliché in particular: I bloody love wild swimming. It started with a simple appreciation for taking a dip in the ocean, but things escalated so fast that I no longer recognise myself. I’m that person I used to roll my eyes at, doing the weekly shop in a dry robe; I have wetsuit boots and sea shoes on seasonal rotation; I bought a waterproof bag that doubles as a luminous swimming float. And, most crucially, I have an app that tells me whether or not the sea where I live will be heaving with human excrement.

This last bit of essential kit is why I am not as overjoyed as I should be at the news that England is to have 27 new monitored bathing spots – the largest expansion of wild swimming areas ever. On the face of it, this is a brilliant thing. The new sites are mainly rivers, and their “designated” status means there will be pollution testing throughout the summer.

But sadly, measuring the cleanliness of places doesn’t actually make them clean. It just lets you know how clean (or not) they are. Environment Agency ratings range from “poor” to “excellent”, with “sufficient” and “good” along the way. Of the current 423 designated spots, 405 met the minimum standard (“sufficient”) for swimming last year. The number of places rated “excellent” has fallen by nearly 6 per cent year-on-year, while the number of “poor” quality spots for 2023 is four times what it was in 2021, hitting a total of 18 last year – the highest level since the four-tier classification system was introduced in 2015.

In the coastal town of Folkestone where I live, the trajectory of the water quality is depressing to witness. In 2021, it scored “excellent”. In 2022, this was downgraded to “good”. Last year, we sank again to “sufficient”. Will it be “poor” for 2024? Can’t wait to find out!

Shropshire swimmer Alison Biddulph, who led the successful campaign to get three sites along the River Severn and the River Teme designated for swimming this summer, has already said she thinks the Environment Agency will rate them “poor” based on her own testing.

“We definitely have issues in the rivers in Shropshire,” she told the BBC. “Not just sewage but also agriculture, and particularly chicken farms. I’m hoping this will kickstart some action locally to clean the waters.”

Designated bathing areas get regular testing to measure their cleanliness from mid-May until the end of September, and are then given an annual overall classification. Samples are analysed to check levels of bacteria – E coli and intestinal enterococci – which in turn indicate the levels of faecal matter in the water. Too much poo? Signs are put up that advise against swimming.

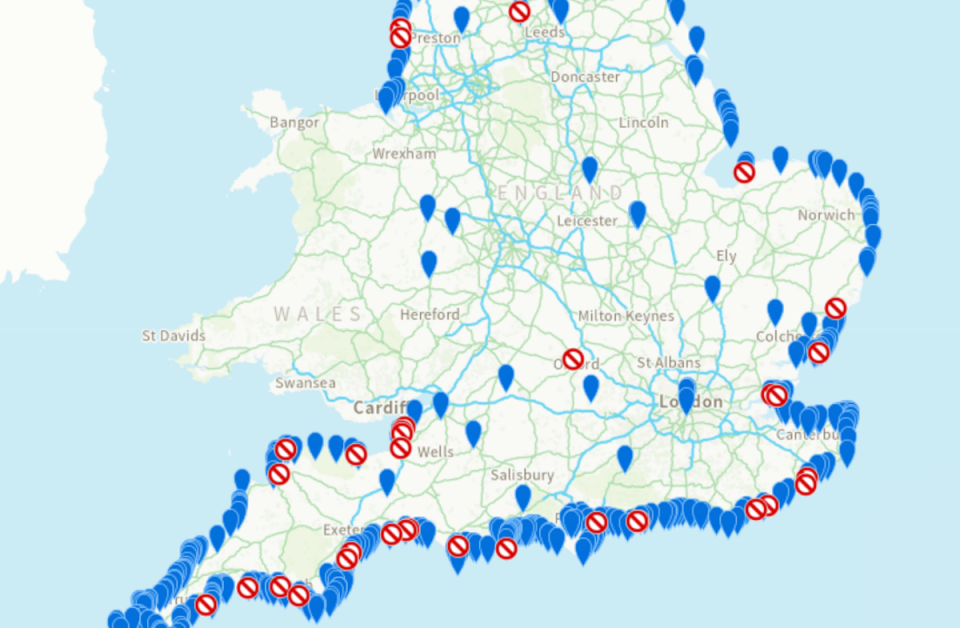

For my part, I stopped checking the aforementioned Safer Seas and Rivers Service (SSRS) app earlier this year, brilliant though it is. It displays a map of the UK, with a green tick or a red cross next to each of more than 450 locations, indicating whether or not to bathe there based on real-time information about sewage discharge and pollution risk. While I used it diligently at first, I soon came to dread tapping on the SSRS icon, all too aware of the disheartening likelihood that my intended dip would be derailed by a scarlet “X”. So I just... opted out. Disgusting, yes – but I preferred blissful ignorance to never getting in the sea again.

It’s not a particularly sensible thing to do, playing fast and loose with your health by ignoring the warnings. Swimming in unclean water can lead to quite the roll-call of ailments: stomach upsets; skin, ear, eye and chest infections; sore throats; hepatitis; E coli. According to an SSRS survey, 55 per cent of Brits who have tried wild swimming or other water sports have reported falling ill afterwards on at least one occasion.

The degradation of UK waters has been steady and insidious

It wasn’t always like this, but the degradation of UK waters has been steady and insidious. As a country, we fall behind 30 EU nations for bathing-water quality, and England has the fifth-biggest share of “poor” quality bathing waters in Europe. Only 14 per cent of rivers meet “good” ecological status, thanks to agricultural pollution as well as sewage, while 75 per cent of rivers tested by SSRS volunteers would be rated “poor” under the bathing waters directive.

Last summer, 57 swimmers famously fell ill at the World Triathlon Championship Series in Sunderland. It triggers a toe-curling, stomach-churning sense of national shame. The world was watching, and what did they see? A country that makes athletes swim in s***. Nice.

Water minister Robbie Moore has claimed to be “fully committed to seeing the quality of our coastal waters, rivers and lakes rise further for the benefit of the environment and everyone who uses them”, while the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs has announced plans to launch a consultation later this year. Proposals to reform bathing-water regulations in England include changes to drive improvements to water quality, more monitoring, and increased flexibility around the dates of the monitoring season. What effect – if any – this will have remains to be seen.

As one campaigner has pointed out, though, getting more swimming spots classed as “designated” is an important step in the right direction (however filthy they may turn out to be).

“It’s in the law that if a designated bathing-water site fails, then the water company, the local authority and the Environment Agency have to work together to improve that water quality,” said Claire Robertson from campaign group Thames21, after Wolvercote Mill Stream in Oxford was designated two years ago and rated “poor” in 2022 and 2023. “If we hadn’t had the designation, we wouldn’t have had the investigation and the promises of upgrades we’ve had.”

Let’s hope the expanded roster of wild swimming areas kickstarts efforts to clean up England’s act. In the meantime, I look forward to a summer spent ignoring my app – and dicing with diarrhoea every time I get in the sea.

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle