Opinion: This cartoon about miscarriage is an important Mother’s Day reminder

Editor’s Note: Roy Schwartz is a pop culture historian and critic. Follow him on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook and at royschwartz.com. His wife, Kimberly Rae Miller, is the editor-in-chief of the parenting magazine MASK and the bestselling author of “Coming Clean” and “Beautiful Bodies.” The views expressed here are their own. View more opinion at CNN.

On Mother’s Day, millions of families around the world celebrate the mothers in their lives, giving them cards, flowers, gifts and taking them out to prix-fixe brunches. It’s a happy occasion, and a good opportunity, like most holidays, to be grateful for what we have. But to truly honor mothers, appreciating the happy parts isn’t enough. Motherhood also involves struggle, and sacrifice, and sometimes sorrow. Those deserve to be recognized, too.

Miscarriage in particular is a chapter in many women’s motherhood story that’s often left untold, and Mother’s Day can be a painful or bittersweet reminder. That’s one reason why cartoonist Chari Pere chose Mother’s Day to release her autobiographical animated short, “Miscarried.”

“Miscarried” is an adaptation of Pere’s 2017 webcomic of the same name, possibly the first comic about miscarriage. It had gotten some press, but went viral when actress Mayim Bialik shared it on her social media. That led Pere, a seasoned illustrator and storyboard artist known for the “Red Bull gives you wings” commercials, to create more comics about taboo topics. She’s creating a “cartoonnmentary” series titled “Unspoken.”

Kim: I experienced my first miscarriage when I was under deadline for my second book, “Beautiful Bodies,” a memoir and social history of our relationship with our bodies and our pursuit of perfection.

I remember calling my agent and telling her I couldn’t write. I couldn’t access the emotions I needed to write about other moments of my life when I couldn’t exist anywhere but the present state of mourning my pregnancy. She shared with me her own experience with pregnancy loss. But she wasn’t the only one; the more I shared, the more people shared with me.

And when I was finally ready to finish the story of my relationship with my body, my miscarriage became part of it.

Roy: When Kim miscarried, I felt shame and guilt, but not for the miscarriage itself. I felt like I was failing her as a husband. My job was to make her safe and happy, and I was utterly helpless to do either. She mostly just wanted to be left alone, like a dying animal in the wild, and I didn’t know how to respect her wishes while also completely ignoring them.

Even worse was the guilt and shame of feeling, and saying, “We miscarried.” She was the one who had to go through it, to carry a dead baby inside of her and then expel it.

She was the one who had to face the stigma, irrational but inescapably internalized, of failing her biological and social purpose. And here I was, feeling loss and grief myself.

It felt selfish, wallowing. Worse, it felt like some version of Munchausen syndrome by proxy, as if I was feeding off her pain, which wasn’t mine to share in.

I was lucky enough to have male friends who were sympathetic and understanding, to different degrees. Several, I discovered, had gone through miscarriages or medically necessary abortions.

One friend, a good guy but a blunt instrument, whose mother went through a stillbirth in the 1980s and carried around the trauma for years, told me, “She won’t get over it until you get on top of her.” It was primitive advice, but he proved to have a point, at least in our case.

Kim: In the months that followed, my perspective on the world became colored by my loss. Between bouts of self-pity and irrational anger, Roy and I started trying to get pregnant again. And when that second pink line appeared, everything just felt better.

In my first pregnancy, I felt something was wrong early on. But in my second, despite all the warnings I encountered online, the same instinct reassured me that everything was going to be alright. And it was. We had a beautiful, healthy boy.

After our son was born, Roy and I experienced five more miscarriages before finally conceiving our daughter. The fact that I already had a child to take care of changed the way I handled those subsequent losses. I didn’t have the luxury of shutting down like I did that first time. In fact, I talked about it even more.

I’ve made it an ongoing quest of sorts to make miscarriage something we talk about openly, so it doesn’t feel so isolating when it happens.

Pere told us that she coped through her art and her faith. She’s a Modern Orthodox Jew, and she found some comfort in the biblical matriarchs’ struggle with infertility, which she discusses in “Miscarried.” Sharing her experience through her art helped her recover from the trauma. “Honestly, the process of putting my story into a comic format was extremely cathartic,” she said. It “removed all of my anger, emotions, and all traces of physical pain.”

Art can be powerfully therapeutic, for both the artist and the audience. Comics in particular can make difficult and taboo topics easier to deal with. They’re often more digestible than prose, which can feel thick and heavy, or even film, which can feel too real and visceral.

In their combination of words and images, comics can also toggle seamlessly between conceptual and corporeal, between the abstract language of a narrative caption and the expressive emotion of a character, creating a balanced experience of thinking and feeling.

In “Miscarried,” Pere makes effective use of her simple, cartoony style to juxtapose against the seriousness of the story, making it more jarring and poignant. That the animation doesn’t have the polish of a high-end production — it was created through a fellowship grant with the Jewish Writers’ Initiative Digital Storytellers Lab — also makes it feel more personal and authentic.

“I wish I knew how many people had experienced miscarriages, infertility issues, or some other form of pregnancy loss while I was undergoing mine,” Pere told us. “I felt relief learning how common miscarriages are, and it wasn’t ‘my fault’ for doing something wrong.”

When it went viral, her comic ended up becoming the resource she’d wished she had. “I still get emails and messages from all over the world,” she said. “[It] motivates me to want to help develop more future content.”

Miscarriage is traumatic, and trauma needs to be acknowledged before it can be healed. It shouldn’t be a taboo topic.

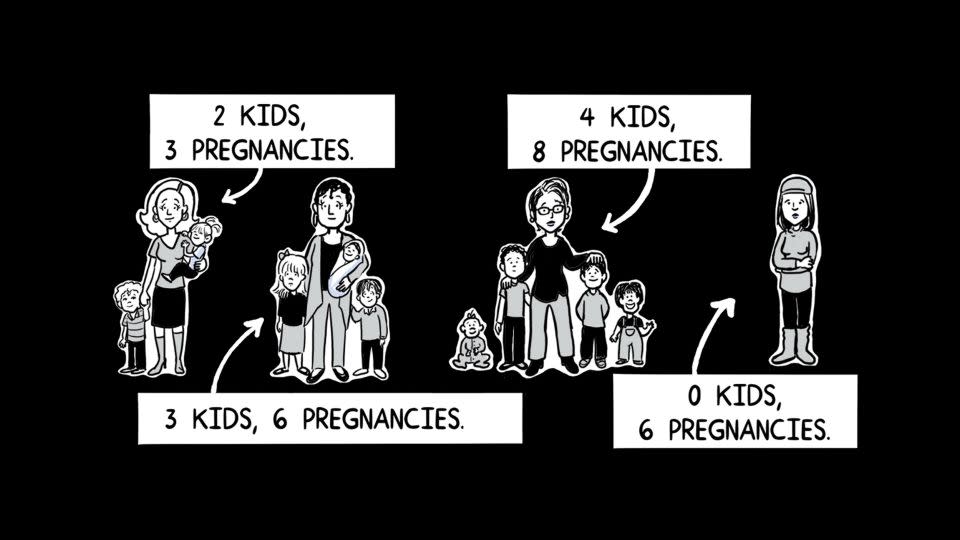

It’s also much more common than most people realize. Up to one in five known pregnancies end in miscarriage (defined as the sudden loss of a pregnancy before week 20) — and since many happen early on, the actual number is likely higher. (More information about miscarriage can be found here, and through most health care providers.)

It’s a deeply personal experience, but that doesn’t mean a woman should go through it alone. Love, support and patience from family, friends and community make all the difference.

Pere’s next two cartoonmentaries are “Michael’s Miscarriage,” an adaptation of her 2018 comic about miscarriage from a husband’s perspective, and “The Diagnosis,” adapting her 2019 comic about having a child with Down syndrome, both based on stories people shared with her. After that, she wants to focus on other challenges of parenting, particularly those involving disorders and disabilities.

“I just hope to use my cartoon and storytelling “‘powers’ to help do good,” she told us. “So that people feel less alone while undergoing their personal journeys.”

“Miscarried” helped remind us of that difficult chapter in our parenting journey, and how talking about it with each other and with others helped us get through it. It’s as much a part of our story as our happy ending of two perfect children. This Mother’s Day, we’ll be honoring that, too.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle