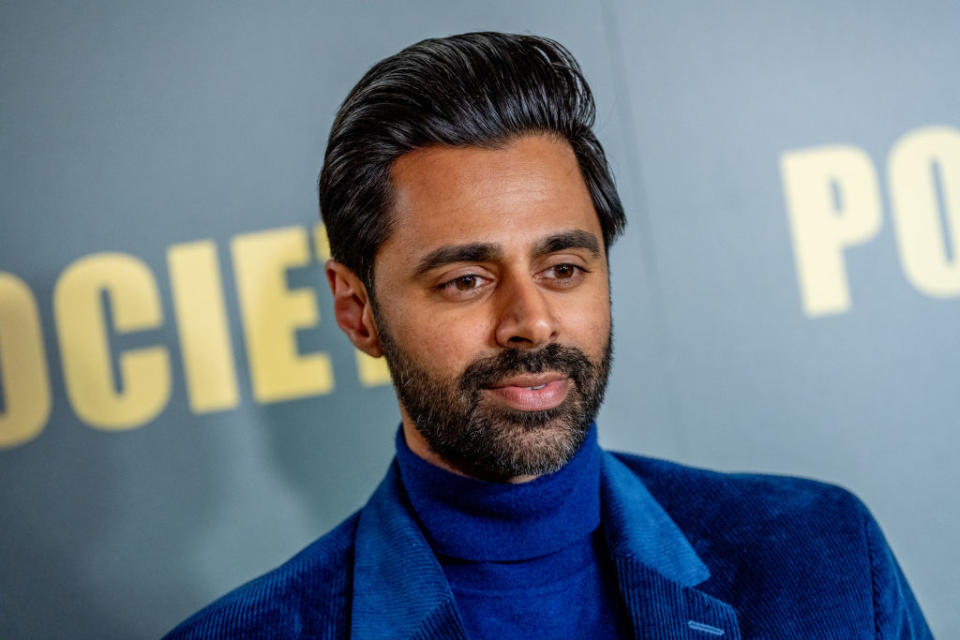

Hasan Minhaj Responded To Claims That He Fabricated Stories In His Standup Material

Hasan Minhaj admitted to fabricating details in his stand-up comedy specials.

For years, the 37-year-old comedian, writer, producer, and television host used autobiographical storytelling and social justice commentary to deliver a brand of comedy that speaks truth to power.

Starting in 2014, he was a senior correspondent for The Daily Show for four years as one of the last hires during the tenure of the show’s second host, Jon Stewart.

In 2017, Hasan released his first stand-up comedy special, Homecoming King, on Netflix, which earned him a Peabody Award the following year.

In 2018, The Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj premiered on Netflix, which earned him an Emmy and a second Peabody Award.

In 2022, he released his second Netflix special, Hasan Minhaj: The King’s Jester.

He’s potentially poised to succeed Trevor Noah as the new host of The Daily Show based on his comedic work that dances in the middle of entertainment and journalism to highlight hard-hitting truths.

And now, in a new profile published by the New Yorker, Hasan revealed that the “emotional truths” in his stand-up specials are actually not true stories.

As the profile explained, Hasan’s projects are known to “blur the lines between entertainment and opinion journalism,” which is a style that The Daily Show popularized.

Other shows that share this style include fellow Daily Show alums: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver and the former Daily Show spinoff The Colbert Report.

Despite the nature of their comedy, these hosts are comedians — not journalists, as pointed out in this report from the Pew Research Center.

But, as noted in the profile, like Hasan, they’ve inserted themselves into the political conversation, so factual information is expected but not guaranteed.

“Every story in my style is built around a seed of truth,” Hasan said. “My comedy Arnold Palmer is 70% emotional truth — this happened — and then 30% hyperbole, exaggeration, fiction.”

Hasan’s comedy relies on his personal experiences as an Asian American and Muslim American man, sometimes using very detailed stories to illustrate the racism and Islamophobia he experienced — and now, we’re learning not all those experiences are authentic.

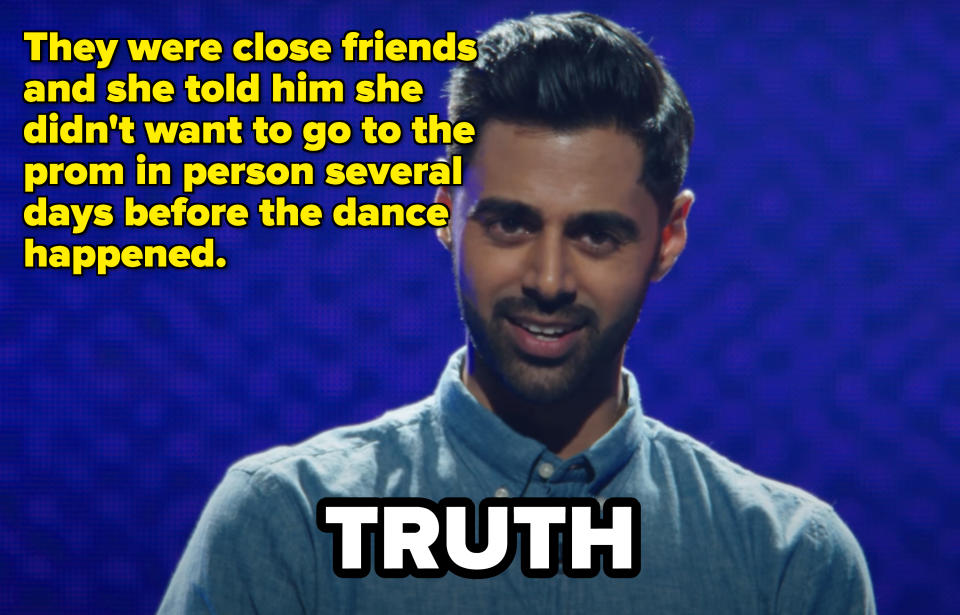

In his comedy special The Homecoming King, Hasan talked about his crush on a white girl who embarrassingly rescinded her invitation to prom at the last minute when he witnessed another boy putting a corsage on her wrist. He claimed he was rejected because her family didn’t want her to be seen with a “brown boy."

The truth: The woman on whom the story was based admitted that while she did turn down Hasan, they were close friends, and she told him in person, days before the dance happened.

Hasan acknowledged she was correct but that they interpreted her rejection differently.

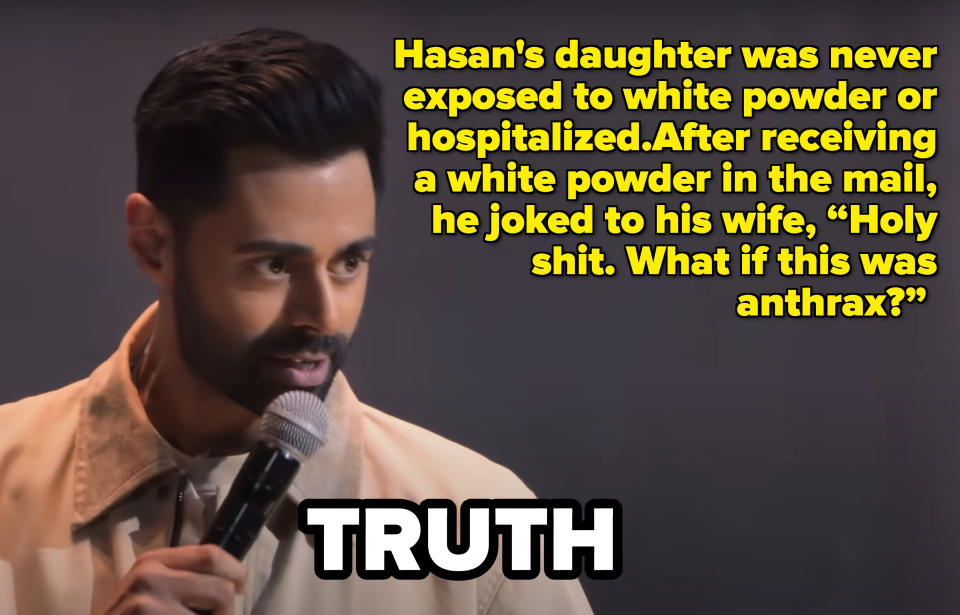

In The King’s Jester, Hasan shared a story of an envelope with white powder, possibly anthrax, sent to his home. According to Hasan, the powder accidentally spilled onto his daughter, and she was rushed to the hospital.

Although the doctor told him it wasn’t anthrax, his wife later said, “You get to say whatever you want on stage, and we have to live with the consequences. I don’t give a shit that Time magazine thinks you’re an ‘influencer.’ If you ever put my kids in danger again, I will leave you in a second.’ ”

The truth: Hasan admitted his daughter was never exposed to white powder or hospitalized. He did maintain that a white powder substance was sent to his home, and he joked, “Holy shit. What if this was anthrax?”

In the same special, Hasan told a story of an FBI informant named Brother Eric, a white Islam convert, who infiltrated his family’s mosque. He claimed the informant attempted to get the congregation to talk about jihad, and the police allegedly arrived and slammed Hasan onto the hood of his car.

The truth: The Brother Eric story was based on a “hard foul he received during a game of pickup basketball in his youth,” as the New Yorker reported. “Minhaj and other teenage Muslims played pickup games with middle-aged men whom the boys suspected were officers. One made a show of pushing Minhaj to the ground.”

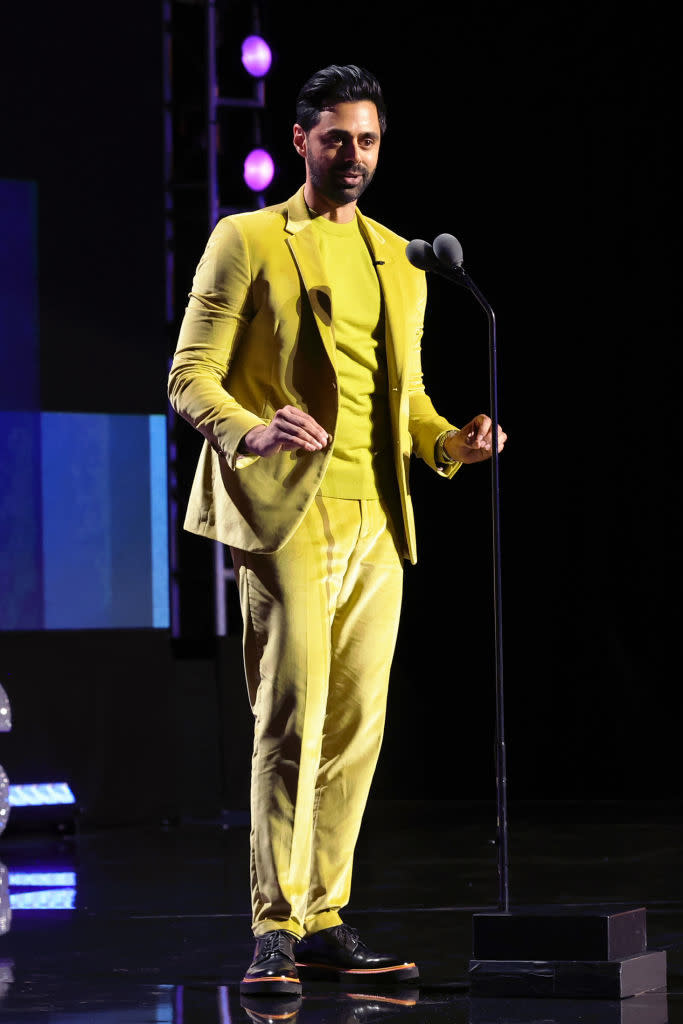

Now, here’s the thing: Hasan acknowledged that his anecdotes are not entirely accurate because his Netflix specials allow him to create characters that serve to tell stories to convey social commentary and “emotional truths.”

In Patriot Act, that same comedic license took a backseat because of the information delivered, and thus, led to audiences being unable to differentiate which Hasan they’re watching.

“Fact-checking at Patriot Act was extremely rigorous.” According to a written statement mentioned in the profile, Hasan said, “A team of news producers fact-checked every line of every draft of every script at least 8-10 times before I ever said anything on camera.”

According to the New Yorker, Hasan insisted the “concocted stories” are justified by the broader points his comedy is trying to convey. “The punch line is worth the fictionalized premise,” Hasan said.

When asked if this is manipulating the audience, he denied that’s the case. “I think they are coming for the emotional roller coaster ride,” he said. “To the people that are, like, ‘Yo, that is way too crazy to happen,’ I don’t care because yes, fuck yes — that’s the point.”

Hasan claims that these fabricated stories are “grounded in truth.”

“I think what I’m ultimately trying to do is highlight all of those stories,” he added. “Building to what I think is a pointed argument.”

“I use the tools of stand-up comedy — hyperbole, changing names and locations, and compressing timelines — to tell entertaining stories. That’s inherent to the art form.”

Whether based on politics, social issues, or personal anecdotes, satirical comedy occasionally takes some creative license in the form of hyperbole, irony, or ridicule. But it shouldn’t be the work of the audience to separate when you’re showing up as a factual commentator or a hyperbolic comedian.

Read the full story here.

Do you think Hasan Minhaj’s “emotional truths” are justified or deceitful?

Let’s talk about it in the comments.

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle