Steve Wozniak and Alex Fielding's startup Privateer aims to be the Google Maps of space

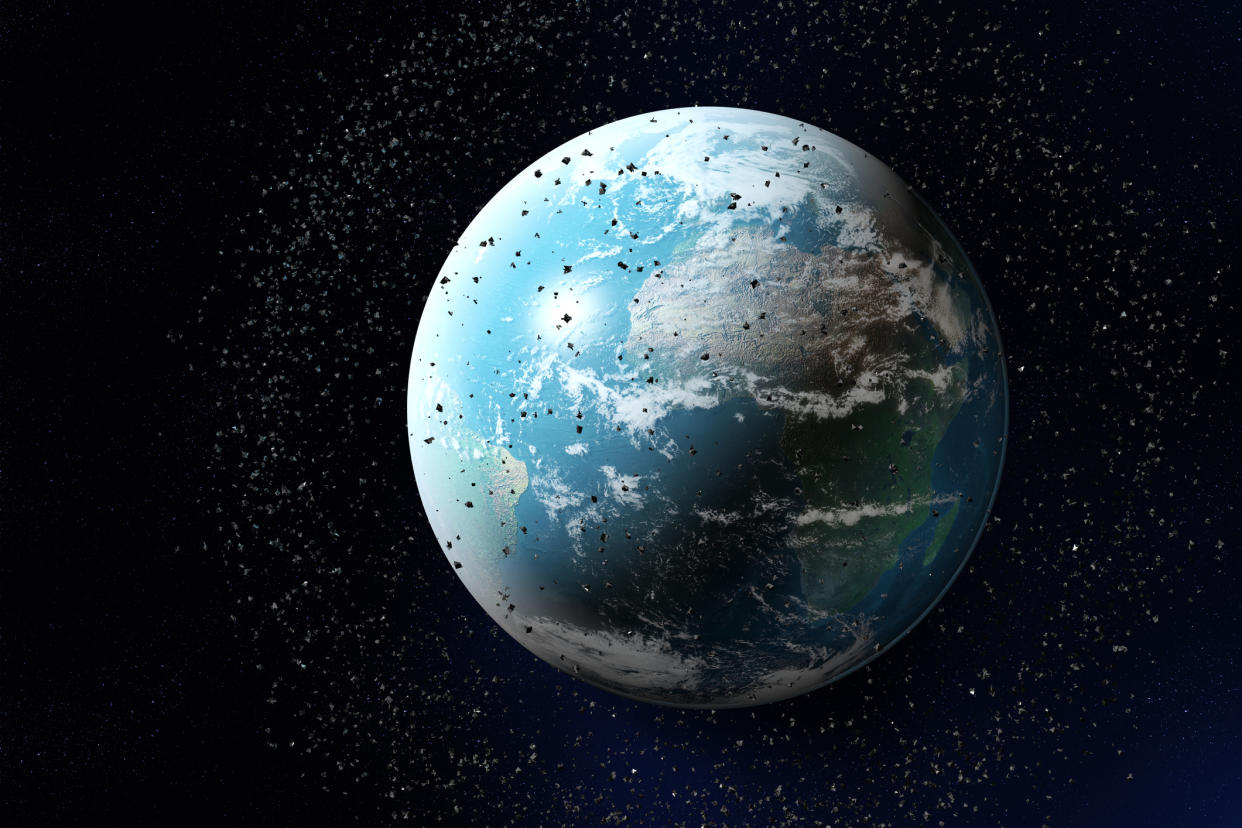

A number of startups have emerged aimed at cleaning up low Earth orbit, which is currently crowded with millions of pieces of space junk -- including anything from broken satellites, to rocket fragments, to debris from vehicle stages or space missions. While the task of cleaning up LEO is an important one, there’s one problem, according to Alex Fielding, co-founder of a new space venture alongside Steve Wozniak: We don’t know where most of the space junk is actually located.

“Orbital cleanup companies, they don't have resolution, or we don't agree on where almost any object in low Earth orbit is with greater accuracy than maybe three or 400 kilometers on any given moment,” Fielding said in a recent interview with TechCrunch.

Fielding and Wozniak are aiming to close that knowledge gap with their new company, Privateer. The company, which has been in stealth, got some attention in September after Wozniak tweeted a link to a one-minute promo video on YouTube, and rumors intensified that Privateer would be focused on cleaning up space objects.

Turns out, that’s not quite accurate. “Privateer actually got started, not with the goal of cleaning up space on day one,” Fielding explained. “We really got started with the goal of building […] the Google Maps of space.”

This is not the first collaboration for Fielding and Apple co-founder Wozniak. The two created Wheels of Zeus in the early 2000s, a hardware company that developed tech to track the location of physical objects.

“When we started that, half of the stuff in space 20 years ago was trash,” Fielding said. The situation has only gotten more dire since. “You're in a world with many, many, many more things [in orbit], of which those many more things are far more dangerous, they're almost all in low orbits, they're moving very, very fast, and they're not well tracked or understood for the most part.”

The dangers of space junk remain all too present. In May, astronauts aboard the International Space Station discovered a five millimeter-wide hole in a robotic arm attached to one of the modules. While that arm remains functioning, the ISS did not perform a maneuver to avoid being hit, which suggests that the object was one of the millions in orbit that are too small to be tracked by the U.S. Space Force’s Space Surveillance Network.

In the same way that launch companies like Rocket Lab and SpaceX are now providing services that used to be the exclusive purview of public agencies like NASA, Privateer could fill in these massive data gaps.

Privateer is hitting the ground running. The company will be sending up its first satellite, dubbed “Pono 1,” on February 11, 2022. The spacecraft, which will be roughly 3U in size (just about half-a-foot), will be equipped with 42 sensors, 30 of which are non-optical and 12 of which are optical cameras. The non-optical sensors will be capable of a precision of as much as 4 microns. The actual body of the satellite will be made of carbon fiber and 3D-printed, using an approach that means it’s a single, solid piece with the same rigidity of titanium, Fielding said. Instead of propellant, it will be directionally oriented using magnetic torquers, a small device that generates electric current for attitude control.

Pono 1 will only stay up for four months, when it will be deorbited and vaporized back in the Earth’s atmosphere. The second satellite, Pono 2, is going up at the end of April. Privateer has already chosen a launch provider and received the requisite approvals for both launches.

In addition to the launches, Fielding said Privateer is already working with Astroscale, an orbital logistics and servicing startup that’s currently demo-ing a space junk removal satellite. Privateer also signed a partnership with the Space Force.

To not pursue a complete Google Maps of space might not just be negligent -- it could be fatal, according to Fielding. “I'm an optimist and I still am very, very, very afraid that we're too late, that we're probably within 24 months of the first on-orbit human space casualty. And the reason for that is just the proliferation in low Earth orbit.”

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle