Sheriff’s office in county where deadly LGBT+ club shooting took place has never used ‘red flag’ law

A 2019 bill that allows judges in Colorado to prevent people who pose a “significant risk” to themselves or others passed the state legislature without a single Republican vote in support.

The so-called “red flag” law was signed into law by Governor Jared Polis, marking one of the most significant gun reform measures passed by state lawmakers in the years after a 2012 mass shooting inside a Colorado movie theatre that killed 12 people and injured 70 others.

But the sheriff’s office in the county where a deadly shooting at an LGBT+ club this week left five people dead, officers have not used the law once.

The shooting inside the Aurora theatre during a screening of The Dark Knight Rises remains the deadliest mass shooting in the state since the 1999 Columbine High School massacre, when two students killed 12 students and a teacher.

But the 2019 law faced overwhelming opposition from not only GOP lawmakers but also sheriff’s offices across the state – including in El Paso County, where five people were fatally shot and 18 others were injured inside a Colorado Springs LGBT+ club on 19 November.

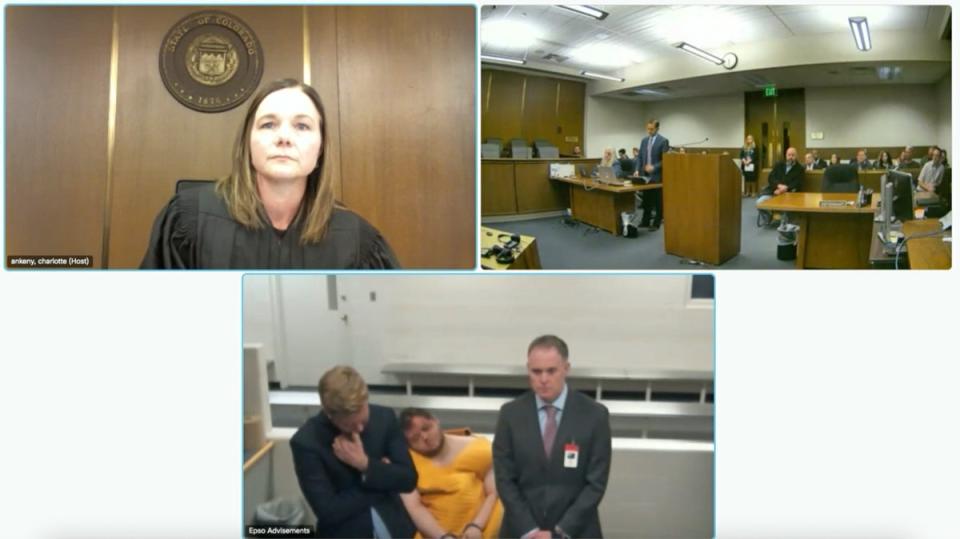

One year earlier, the suspect accused of immediately opening fire into the club that night was arrested on felony menacing and kidnapping charges, which were later dropped.

Not only did the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office not pursue an order to seize firearms from the suspect, Anderson Lee Aldrich — the county has never once initiated a seizure.

Since the law went into effect in 2020, the office has never pursued or initiated a judge’s order to temporarily seize a firearm from a person deemed to be a significant risk to themselves or others.

Sgt Jason Garrett, a spokesman for the sheriff’s office, told The Colorado Sun on Wednesday that the agency has never sought an extreme risk protection order – or ERPO – as outlined by the 2019 law.

Under the law, a judge can issue an ERPO if a petitioner – including law enforcement – can show that a person “poses a significant risk of causing personal injury to self or others by having in his or her custody or control a firearm or by purchasing, possessing or receiving a firearm.”

Data reviewed by The Colorado Sun found that the state received nearly 300 requests for temporary ERPO seizures and nearly 100 requests for extended orders statewide since the law went into effect.

A majority of the requests came from law enforcement agencies.

Following the law’s passage, the Board of El Paso County Commissioners voted to adopt a resolution to formally oppose the red-flag measure.

Commissioners pledged to “actively resist” the legislation, committed to “legal action if warranted”, and invited “all like-minded counties” to join the county’s opposition, according to the resolution.

The commissioners also vowed against the appropriation of “any funds or resources to initiate unconstitutional seizures” and pledged to collaborate with El Paso County Sheriff Bill Elder, who personally opposed the law.

Sheriff Elder has issued more than 45,500 concealed carry permits to citizens and retired peace officers, according to the county, which noted that the sheriff has issued more permits “than any other sheriff in the state.”

More than half of Colorado counties drafted similar “Second Amendment preservation” resolutions.

In 2019, Sheriff Elder said he opposed the law because “we’re going to be taking personal property away from people without having due process.”

“The sheriff’s office isn’t going to run over and try to get a court order,” he told local NBC affiliate KOAA News.

It is unclear whether Aldrich’s 2021 case could have been eligible for an extreme risk protection order, which would likely have expired by the time of the Club Q shooting.

In June 2021, his office arrested Aldrich on felony menacing and kidnapping charges after a woman reported that a person she said was her son “was threatening to cause harm to her with a homemade bomb, multiple weapons and ammunition.”

According to The Colorado Springs Gazette, the El Paso County District Attorney’s Office decided against pursuing formal charges. The case was subsequently sealed.

“There is absolutely nothing there, the case was dropped, and I’m asking you either remove or update the story,” Aldrich said in a voice message left for an editor at The Gazette in August, according to The Associated Press. “The entire case was dismissed.”

A lack of witness cooperation prevented a prosecution, according to law enforcement officials speaking to The New York Times. Officials have repeatedly declined to publicly discuss that case.

“These laws were put on the books exactly to address the dangerous behaviors that are often precursors to larger violent events,” according to Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions professor Shannon Frattaroli, speaking to Reuters.

“Threatening to blow up your mother or the neighborhood most reasonable people would agree is a signal that some intervention is needed,” she said.

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle