NFL defenses have been getting first and second down wrong. Here's how they can fix it

By Seth Galina

We get it, NFL defenses, you can stop the run. From alignment to scheme to mentality, the history of defense has been told first by killing run plays, and only then talking about defending the pass.

Over the past two seasons on first and second down, 61 of 64 team seasons produced a negative EPA (Expected Points Added) per play against the run. Of course, of the same 64 team seasons, only 10 produced a negative EPA/play against the pass. All of this stopping the run is having a tremendously bad impact on trying to stop the pass.

Congratulations, NFL defenses. By plugging one gap, you’ve opened up many new ones. Surely a better balance needs to be struck.

Just more than 65 percent of all snaps on first and second down are played in what’s called “one high safety,” as opposed to “two high safeties.” There are only so many gaps for an offensive player to run through with the ball, so by having a defender responsible for each gap, you can stuff running plays much easier.

This is the forever dilemma in football. If you play with two safeties, you are susceptible to being run on, but if you play with one safety, you are susceptible to the vertical passing game. Here at PFF, we have extolled the virtues of the passing game in modern football. We think you should allocate resources to stop the pass.

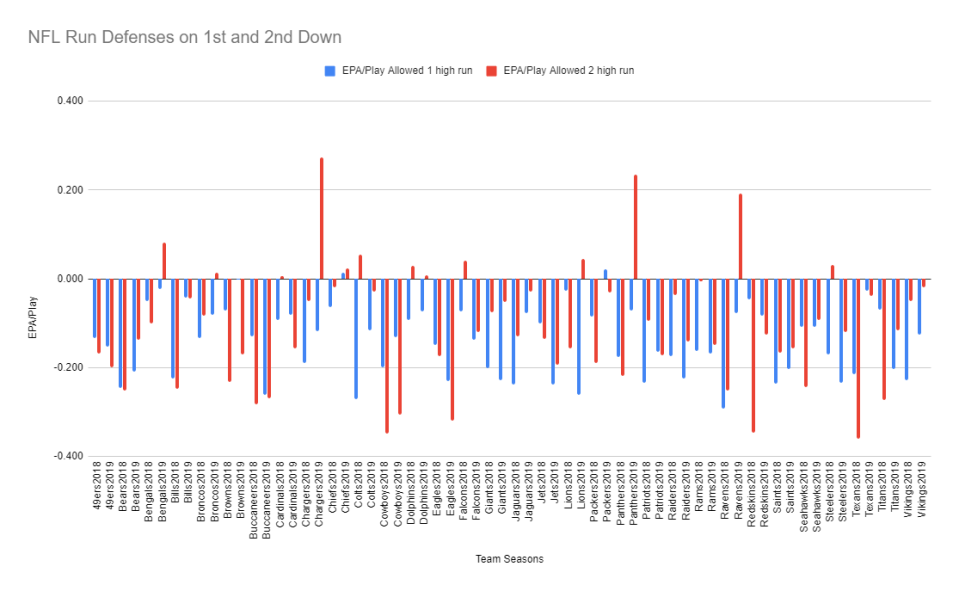

Here is the team difference in stopping the run on first and second down the last two seasons whether the team played one-high or two-high:

Most teams can stop the run no matter how many safeties they drop. Even though teams want to load the box on early downs to stop the run, they might not necessarily need to. Teams can still stop the run with two high safeties — the question is whether they are stopping the pass better as well.

To a certain degree, they are. Twenty-one team seasons produced a negative EPA/play against the pass in one-high, while 29 produced the same results in two-high. Thirty-seven of the 64 team seasons saw an increase (or only a negligible decrease) in ability to defend the pass from two-high.

Whether it’s because the NFL’s current one-high meta is slowly becoming overexposed or our ideas about how to stop offenses have been wrong all along, the NFL could stand to ease up a little on loading the box. By playing more two-high, you can “steal a down” by giving the offense a look it wants to run against but still get a stop.

Playing a two-high structure in the current spread climate of the NFL presents many challenges. Here are some ways that defenses are dealing with it.

Who played two-high defense best?

The 2018 Houston Texans were the best two-high run defense of the past two seasons, and having two elite players on the defensive line was one of the major reasons why.

In two-high, you need to find a way to “steal” gaps. The easiest way to do this is to have your defensive line get off blocks and make plays. Jadeveon Clowney posted the second-highest single-season grade in run defense for a player designated as an edge defender or defensive interior linemen at 91.3. His running mate J.J. Watt posted the 22nd-best grade at 81.5. One out of every four “defensive stops” by the Texans that year were made by one of these two players.

Schematically, the Texans did a good job moving pieces around, allowing Clowney to stand up and get a running start at the offensive line. For Watt, there were a lot of quick moves to beat offensive linemen right from the jump, but this play against the Jets shows him controlling the offensive tackle before falling back inside and tackling the runner.

Technically, Watt is the supposed to control the “C-gap” outside the offensive tackle, but since the Texans are “out gapped,” nobody has the “B-gap” inside of him — so Watt knows he has to play both:

Watt is playing a technique called “two-gapping.” This is where a defensive lineman has to control two gaps because the box isn’t loaded and they don’t have enough players for each gap.

Gone are the old days of big burly defensive linemen lining up directly in front of their OL counterparts and playing two gaps. As the NFL continues to throw the ball more and more on early downs, to get a better pass rush, defensive linemen need to play on the shoulders of the offensive linemen.

How the Cowboys stuffed the run well in 2019

Whether or not you have good defensive linemen, one of the common used tactics in a two-high world is to stunt your linemen. Sometimes it’s just one player moving to a different gap than the one he was originally lined up in, or a “game” between two linemen exchanging gaps.

Doing this helps free up the linebackers to run clean and make tackles and can cause confusion between the offensive linemen regarding who to block. Stunting defensive linemen into a gap that was originally occupied by a linebacker allows that linebacker to sit tight and read the play before attacking. It also messes with the interior of the offensive line. Three offensive linemen often end up just taking two defensive linemen, freeing up other players.

The Dallas Cowboys, who were the best two-high run-stuffing team of 2019, stunted their front almost every play in two-high. In this play against New Orleans, the two defensive linemen closest to the near sideline cross their offensive players' faces on the snap, which allows Jaylon Smith the ability to feel out Alvin Kamara’s path and make the stop:

RPO presents new challenges on early downs

As RPOs become more prevalent in the modern game, more issues reveal themselves. In a spread 2×2 set, if you want to cover both slot receivers, you only have five players in the box.

One of the solutions to get the extra player back into the box is to “sling the fits.” The idea is that the linebacker who the quarterback is not looking at for the RPO can add himself back into the box. The linebacker who is being looked at will freeze and take away the pass option, forcing a run.

NFL offenses still want to run the ball on early downs, so playing two-high — and allowing a run — and then stopping it while still being strong on the back-end might be the wave of the future. The NFL defense is due for a schematic evolution anyway. We’ve been living in a one-high world for long enough. It’s time to mix things up.

For more statistical NFL analysis, go to PFF.com.

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle