Glenallen Hill's Wrigley Field rooftop homer traveled over the stands and into imaginations

Ask enough folks to point to a spot 450 feet away, 500 feet away, and you’d get everything from the end of the driveway to the tip of a cumulus cloud. They could do it in a ballpark. They probably could point to the exact seat.

It’s a long way to hit a baseball. That far, looking toward home plate, from there to here. And, well, that’s about it.

But, launching a ball into a parking lot or into the trees or over the pool, that’s something. Hardly any kid ever bragged, I’m gonna hit this ball 500 feet! No, what they said is, I’m gonna hit it over the garage! I’m gonna hit it over the hedge! I’m gonna hit it over Mrs. Abernathy’s car!

Or, maybe, I’m gonna hit this ball over the fence, over the bleachers, over the street and — see that roof over there? — onto that.

There’s no arguing the roof.

Twenty years later: See that building? Well, your daddy hit a ball up onto that roof there once. Yep, it’s true.

Long as there’s a building, there’ll be a roof, and there’ll be a story to tell.

When they remember some special day, some special swing, would you rather have hit a home run or put one over The Monster? Or hit it into the fountains? Into the monuments? Into the bay? Into the freakin’ river?

Or, perhaps, on a cool Thursday afternoon 20 years ago today, onto the roof of a five-story, yellow brick building at 1032 W. Waveland Ave., located across the street from Chicago’s Wrigley Field.

The building went up in 1909. The ballpark opened five years later. In game conditions, the roof has been reached one time.

Twenty years later, Glenallen Hill has never been to the roof he made a little more famous. He does not possess the baseball he hit onto that roof. His son, 19-year-old Glenallen Jr., only recently saw the video of that swing and what resulted from it, and not because his dad showed it to him.

[Meet the man who has the baseball that Glenallen Hill deposited on the roof]

His voice is deep, bottomless, as though his words are rising from the earth. Reflecting that effort, perhaps, he wastes few.

He is 55 and, after managing the Colorado Rockies’ Triple-A teams for seven seasons, wondering what’s next. The Rockies declined to renew his contract after 2019.

“I guess that means I was fired,” he says.

Hill played 13 major league seasons and, before those, six minor-league seasons. He coached. He managed. He raised a family. That’ll fill 55 years pretty well. That’s a lot of life, a lot of baseball.

The phone rings, as it does every so often, and what he’s asked about is a single moment, a single swing, a ball and a rooftop and a young man in a green windbreaker with a plastic cup in one hand and the symbol of that moment in the other, raised overhead.

“Naw, it’s OK,” he says. “It’s important that people talk about it. They want to know what it felt like.”

He pauses and a low rumble becomes a chuckle.

“Here’s the thing, my man,” he says. “I’ve been hitting long home runs since I was playing baseball.”

Up comes the rumble again.

The view from the mound

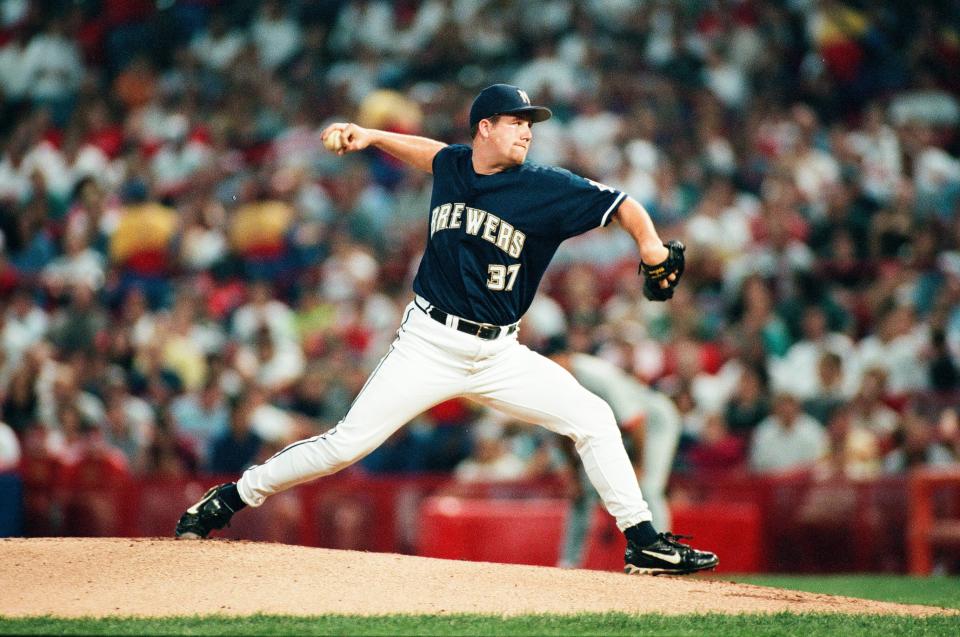

Steve Woodard, a right-handed pitcher for the Milwaukee Brewers that afternoon, walked from the mound to the dugout after the second inning. He didn’t ordinarily talk much, which teammates took for shyness, so they let him be, especially when he was pitching. But, when he reached the dugout steps that day, Woodard recalled it was probably fellow pitcher Bob Wickman who greeted him: “You know that ball landed on the roof.”

“No it didn’t,” Woodard replied.

“Yeah it did,” Wickman said.

“C’mon,” Woodard said.

Well, he thought, that was probably what had gotten the crowd so excited.

And now, years later, hundreds of good-natured reminders — “You gave up that home run, huh” — later, he sort of wishes he’d turned to watch it go, being as he was the only one in the ballpark who hadn’t.

Lyle Mouton, the Brewers left fielder, lunged a couple steps back and gave up. Henry Blanco, the catcher, raised his eyes to the sky. Third baseman José Hernández gaped over his left shoulder. Shortstop Mark Loretta over his right.

Almost before Hill left the batter’s box, Woodard held up his glove to the umpire. He’d require a new baseball.

Not that long ago, his stepson, 18-year-old Parker, had some friends over at Woodard’s home in Hartselle, Alabama. They were watching television when a clamor — “Oh my gosh!”, “What!?”, “You see that?” — arose in the room, bringing Woodard from the other side of the house. The boys had discovered the home run. The roof.

Woodard laughed with them.

“Hey, until you all get to the big leagues …,” he scolded.

It slowed them none at all.

Thing is, Glenallen Hill did that to Steve Woodard plenty. In nine at-bats, Hill homered four times and doubled once. His final six plate appearances against Woodard — Hill’s final major league game was in 2001, Woodard’s was two years later — went home run, home run, home run, double, intentional walk, home run.

“Like his bat had a magnet to the ball,” Woodard said. “I’d throw it and just look at it and think, ‘My gosh.’”

But not in Chicago that afternoon. The sound of it would do.

“I tell people that’s a top-15 home run right there,” he said, amused. “You know, you sometimes wish, I mean, you take things for granted when you’re playing. Like it’ll always be there. Maybe we should’ve enjoyed it more.”

After a moment, he added, “Man, I miss all that.”

‘It was a question of how small that ball was going to get’

The count was two balls, no strikes. Bottom of the second inning, one out. The sky was gray, a helping wind to left. It was going to be one of those days at Wrigley.

Blanco, the catcher, waggled his right forefinger. He touched the inside of his left thigh, asking for a sinker, inside. The pitch started in the middle of the plate, then oozed right, as though it were chasing Hill’s bat barrel.

Hill dropped his hands to about waist high and attacked with a short, flat swing. He finished low across his body, a familiar swing that would generate 186 career home runs and that was uniquely his. He liked to think about swinging a hammer, how he’d keep his hands soft and loose, the way he’d watched Jack Clark and Willie McCovey do it when he was growing up in Santa Cruz, California. What he chased was the sound the ball made off their bats, the sound of the impact, the way it echoed in his ears and across a ballpark. Dave Winfield made that sound. Sometimes, Glenallen Hill did, too.

Cubs second baseman Jeff Huson, on the rail in front of the third-base dugout, reached for the guy closest to him. It was shortstop Ricky Gutierrez. Huson grabbed his arm and wouldn’t let go, both of them leaning, looking into the gray sky, trying to follow a baseball that seemed destined for somewhere ridiculous.

“You’ve heard that a ball sounds like it was shot out of a cannon,” Huson said. “This was an even deeper sound than that. There was no question it was going to go out of the stadium. It was a question of how small that ball was going to get, and how fast, like it was in orbit.”

Loretta, the Brewers shortstop, had five hits that day. End to end, it seemed in retrospect, they’d reach the roof.

“I remember the sound,” he said. “That was the most impressive home run I’ve ever seen live. Talk about launch angle. That swing was as flat as could be. He chopped that thing onto the roof.”

As bench coach for the Cubs last season, Loretta lived up on Halsted Street. His walk to the ballpark took him down Waveland and through the shadow of that building. More than once he’d looked up and thought about the ball that landed up there, the swing that generated it and the man who’d stomped past him at shortstop a few seconds later. He’d been a Brewer in 1998, in the same division as Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa when they’d combined for 136 home runs, 16 against the Brewers (12 by Sosa). Still, he’d never seen anything quite like what Glenallen Hill had done.

When the ball had landed, Loretta gazed at Hernández, the third baseman, and they shared the same expression: Can you believe that?

“You know the ball’s crushed, just crushed, but when it lands in the stands across the street, I mean, those places are just unreachable,” he said. “I couldn’t get it there from second base.”

‘My expectation was to create that sound’

From 1989 to 2001, Hill played for seven teams. He played for the Cubs twice. He was never an All-Star. He batted .271. In 2000, two months after the home run, he was traded to the New York Yankees, for whom he hit 16 home runs in 40 games and was part of a World Series champion. By June of the following year, his career was over.

For about the first time since then, he is home with his family for the summer, waiting out the coronavirus like everyone else. Glenallen Jr., a middle infielder, was drafted in the fourth round by the Arizona Diamondbacks last June. Recently, Junior got into that old box of video tapes and there was his dad, sunglasses on, waiting on a two-and-oh sinker from some right-hander at Wrigley Field. He doesn’t spend a lot of time talking about himself, so maybe that’s the part of this Hill doesn’t love.

“My expectation, always,” he says, “was to create a sound that could be heard in the stadium. Whether that ball left the ballpark or not, my expectation was to create that sound.”

Besides, he says, somebody will do it again one day. Whether it’s 470 feet to that roof or 500 feet or more, whatever they say it is, that roof can be had. Loosen the hands, throw the hammer, make the sound …

Then feel the air get sucked out of the place.

Asked if he were proud of that home run and all the memories it evokes, Hill sighs and says, “No. Because it wasn’t a surprise. It was something that I did all the time.”

In batting practice, he’d hit the building with the Budweiser sign on it all the time, and that was in left-center field. Heck, he’d hit it over that building. Then there was that game in Buffalo, back in the minor leagues, and he’d maybe never hit a ball harder or farther than he did that day. He could still see that ball go.

“The longest ever?” he says. “That one.”

Five-hundred feet? Five-fifty? More?

Glenallen Hill laughs, good and low.

“Onto the freeway, my man,” he says.

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle