Extended netting serves a worthy purpose but some fans aren't on board yet

CHICAGO — Margaret Blomstrand was the first to descend. At 5:43 on a picturesque evening, down the steps between sections 147 and 148, into her seat for a first glimpse. And when she got it, for at least a minute, she wouldn’t let go.

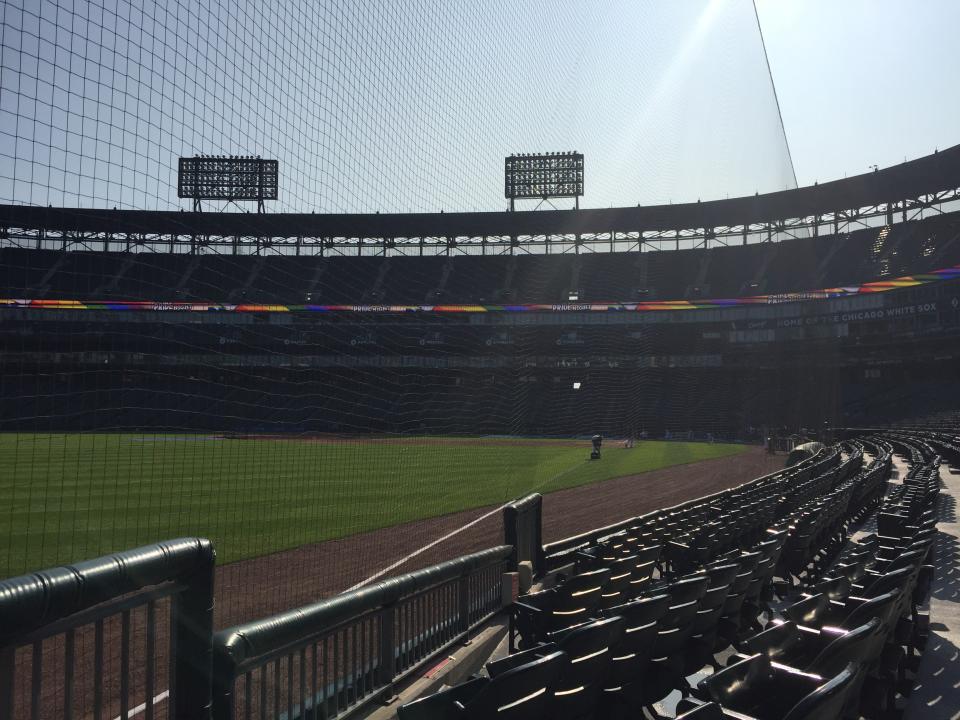

Blomstrand, you see, has been coming to Major League Baseball games for a few decades. She and her husband have been Chicago White Sox season ticket holders for several years. And on hundreds of spring, summer and fall nights, their view has been a familiar one. The immaculate green. The crisp sandy-brown. The two-plus tiers of dark seats illuminated by sunlight or floodlights. Unobstructed.

But this summer night was different.

On Monday, the White Sox became the first MLB team to host a game with protective netting stretching from foul pole to foul pole.

“I am looking at this,” Blomstrand said a day later after surveying the scene. “And I don’t like it.”

Nor was she alone in her distaste. Her husband, who joined her three minutes later, was more blunt: “It sucks.”

The netting, of course, serves a purpose. Guaranteed Rate Field is now indisputably safer than it was last month, when a foul ball off the bat of Eloy Jiménez struck a woman in the head and sent her to the hospital. For fans, risk of a repeat is now almost non-existent.

Many of them, however, have mixed feelings about their team’s groundbreaking innovation. Whether they arrived 90 minutes prior to Tuesday’s first pitch or 15 minutes after it; whether as grandfather and grandson or as a group of teens; whether to Yahoo Sports or amongst themselves, they came ready to talk about it. And their opinions varied wildly.

Why the White Sox extended the netting

Yahoo Sports spoke with over 30 fans before and during Tuesday’s 5-1 White Sox loss to the Marlins. A common thread throughout a majority of the interviews was the word “understand.” Or a synonym. Or a reasonable sentiment: I don’t like the netting; but installing it probably makes sense.

“They need to do something,” said Steve Hussey, who attended the game with his grandson. “If this is what they have to do to protect people, then so be it.”

Spend an inning or two down the right-field line, and you’ll understand why. Two young brothers scurried up and down the aisle, in and out of parents’ laps. Three petite sisters were more concerned with cotton candy than the game. As they dragged their mother up to the concourse, a Marlins home run soared over the right-field wall. They didn’t even turn around.

They, if not for the netting, would be susceptible. So would the elderly. A 2-year-old has been hit and hospitalized. A 79-year-old has been killed. And as veteran outfielder Curtis Granderson pointed out to Yahoo Sports before the game, the viral moments are by no means the only ones throughout the majors and minors: “The stories that we’ve seen that get national coverage are just a few [of many].”

All of which is why the White Sox barely consulted fans before making the decision to extend the netting. “It was top-down driven,” SVP of communications Scott Reifert told Yahoo Sports. “[Team owner] Jerry Reinsdorf actually reached out to our stadium operations folks ... and said, ‘Hey, investigate this, see if you can do it, and then how long would it take to get done.’” After the 2-year-old’s hospitalization in Houston, he decided it was time. Over the All-Star break, the White Sox stadium ops crew went to work.

On Tuesday, even kids understood. John Pastewski, a native Southsider, and his three sons arrived over an hour before the game, to the best seats they’d ever bought – a few rows back, one section to the left of the White Sox dugout. “Too many injuries,” the oldest of the three said, concurring with his dad that the netting was the right move. They didn’t think it would affect their enjoyment of the game.

“I just want to get a ball,” the middle sibling said – only to quickly realize that the netting, for that purpose, might be problematic.

“That’s the only thing,” Pastewski said. He used to come to games and get autographs in his youth. “With this, now, you can’t, really.”

Pregame autographs are unwieldy and inefficient

Shortly before 6 o’clock, with seats along the third-base line still largely empty, an on-field security guard strolled over to the netting and expressed one of two main concerns. “I do want kids to still have access,” he said to two fans in the second row. And the pole-to-pole netting impedes some of it.

Robert Kolodziejski has been going to Sox games since the Minnie Miñoso days. His son, Robert Jr., has been coming along for as long as he can remember. They used to come early. Plead for autographs. Convince players to give them balls.

“But you can’t do that now,” the elder Kolodziejski says. “You can’t even hand the ball through there to get it autographed.”

Sure enough, as first pitch approaches, kids grow anxious. One wearing a Tim Anderson jersey tucked into silver athletic shorts, and near-knee-high white socks, stands waiting. One tiny hand clutches a baseball, the other the netting. Another kid in a Jose Abreu jersey comes careening down the steps to join him. Ian Yeazel and his dad, Jamie, are ready to pounce as well. Pretty soon, there’s a miniature congregation ... but no player to appease it.

bUt HoW aRe KiDs GoNnA gEt AuToGrApHs If ThEy ExTeNd ThE nEtTiNg pic.twitter.com/6g6kdIAb4W

— Henry Bushnell (@HenryBushnell) July 24, 2019

Then, five minutes before the national anthem, Abreu saves the day. Kids slide sharpies to him through the net. Balls won’t fit, but Abreu reaches through to hold them and signs from the other side.

The process, though, is unwieldy and inefficient. Ian comes away empty-handed. He gets AJ Reed’s signature 10 minutes later, but his father, Jamie, comes away saying: “Definitely tougher to get autographs.”

And the one they did get seemed, at least to them, somewhat slapdash:

No kid along either foul line, at least that I saw, got a ball tossed to them over the net. Which, of course, affects only a small fraction of those in attendance. But it’s part of a broader issue.

As a teenage fan named Ricky said: “Watching the game is fine. It’s just the [fan-player] interaction, you’re not getting any of that.”

Then there are those who are completely content to enjoy nine innings without that interaction. “I mean, you don’t catch a few balls, that’s fine,” diehard Sox fan Cris Ortega said. “You save hospital bills.”

And what about whether the netting affects his view of the action?

“You see the lines,” Ortega said. “But I’d rather be safe and have my face intact.”

Said Hussey, the grandfather, an hour before first pitch: “It’s not gonna affect the game.”

The netting is ‘10 times worse in person’

But for some, it did. I plopped myself down in section 120, on the first-base line, to the right of the visitors dugout, for the first three innings. A group of four men arrived during the bottom of the first, and spent more than two full frames talking – and mostly complaining – about the netting.

“Yeah, this is not the same,” one said. He reiterated as much in voice-dictated text messages. “I was kind of wondering how this would look”—one of the other four cut him off: “It doesn’t look good at all.”

And a third, who said his buddies were texting him after seeing the netting on TV: “It’s 10 times worse in person.”

A second group of three guys arrived and took seats behind them. Their chatter immediately turned to the same topic. Both groups agreed that sitting farther up would be preferable, which was a common opinion. The Blomstrands said that if they chose to renew season tickets, they’d nab less expensive seats farther away from the field. Others had similar thoughts.

Farther down the line, a few sections from the right-field foul pole, Dan and Ann Faragoi weren’t impressed with their view either. They and their two young kids usually sit in the first row. They’d moved back a row. Dan had heard the company line: After three minutes, you won’t notice anything. “That’s not true,” he assures.

“It’s almost like it was being shoved down your throat: ‘There’s no difference, you’ll never notice, this is a great thing.’”

“Oh no, we notice,” Ann said.

And Dan: “We notice. You feel like you’re in a cage. It wouldn’t stop me from coming, but it would stop me from sitting so close."

The closer fans were to the net, and the farther they were away from home plate, the more the netting affected the experience. Liz Marienthal, who was sitting off the left-field line, compared the “bizarre” view to “having almost like a tic-tac-toe board in front of you.” Many wondered why it had to be extended all the way to the pole. The Faragois, who’ve had those seats for six years, said there’d “never been anything close” to a safety concern, even with a pair of youngsters in tow.

And even some who expected to be unbothered by the netting came away complaining. Remember Hussey, who’d said it was “not gonna affect the game”?

“The netting ruined the game,” he said in a seventh-inning text message. “It was hard to look through it.”

‘Imagine if that was your face’

The whining was plentiful. Several fans moaned that they were being punished for the negligence of others glued to smartphones – and that the phone addicts simply shouldn’t buy tickets in the line of fire. (Though some, as they moaned, weren’t paying attention to the game themselves.)

Others had a legitimate gripe. “It’s another further separation between the fan and the game,” said Kolodziejski down the third-base line. His words were echoed almost exactly by another fan, Brian Wright, down the first-base line.

“It definitely puts a barrier between us,” said Ann Faragoi, who mentioned that former Sox outfielder Adam Eaton used to interact with her children over in the right field corner.

But Granderson, speaking in the clubhouse three hours pregame, said that interaction can live on. “Yesterday, when I came out and was signing autographs ... there was netting there, and it didn’t deter the fans from coming down,” he explained. “They wanted to still ask for photos. I was still able to give guys pounds and things like that. Even the autograph guys were still able to slide their cards through.”

Oh, and he’s got a story to tell. “One of the [fans] said, ‘Man, this netting sucks.’ I said, ‘OK, but it’s either that or getting hit in the face.’ He goes, ‘Aw, yeah, that’s right. But it’s all those people on their phones.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, but I’ve seen a lot of people that get hit that weren’t on their phones.’ So then he said, ‘Well, I caught a foul ball once, and I hope this doesn’t get in the way. But when I caught it, my hand, it was hurting.’ I said, ‘So imagine if that was your face. That’s what this is for.’”

Or, more broadly, it’s for people like Chad Tompkins, a middle-aged dad of two who wore a Paul Konerko jersey and sunglasses perched atop his hat to Tuesday’s game. He and his wife had bought first-row tickets off the right-field line. His kids were decked out in Sox gear. They were one section away from the Faragois, who said they “understand,” the netting, “but aren’t fans” of it. So what did Tompkins think?

“Actually, it was a big reason we decided to buy these seats,” he said. “With young kids, we knew this would be a great place for them to be able to sit and still be safe.”

– – – – – – –

Henry Bushnell is a features writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell, and on Facebook.

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle