Before Colin Kaepernick, there was the Ferguson Five

Chris Givens couldn’t stay silent any longer.

At a time when many NFL players worried that speaking out would jeopardize their careers, the third-year St. Louis Rams receiver felt he had to say something to condemn racial injustice and demonstrate he was part of the fight for change.

It was November 2014, and a Missouri grand jury had just declined to indict a white Ferguson police officer for the fatal shooting of unarmed Black teenager Michael Brown. The decision that there wasn’t sufficient evidence to file criminal charges ignited demonstrations from New York to Los Angeles and unleashed days of peaceful protests, rioting and looting in Ferguson, Missouri.

Brown’s death resonated deeply with the Rams because Ferguson was only 10 miles from their practice facility. Some of the players and coaches lived so close to Ferguson that from their balconies they could see smoke rising from burning buildings and squadrons of police cars screaming down the freeway.

Among the Rams shaken most by the tragedy was Givens, a mentor for St. Louis kids who told him they saw themselves in Brown. Their fears that their skin color put them more at risk during an encounter with the police motivated Givens to approach teammates about ways to use their platform to highlight the need for reform.

“We believed we had an opportunity to shine light on a situation we felt was severely unjust,” Givens told Yahoo Sports. “We wanted to be a voice for the people in Ferguson. They were our fans. They supported us. We were trying to support them through a moment of crisis.”

It may now be more routine than incendiary for athletes to speak out on polarizing social issues, but six years ago that was not yet the case. In 2014, Colin Kaepernick had not yet kneeled, LeBron had not yet found his voice and the Bucks had not yet walked out. An athlete dabbling in political activism often had more to lose than to gain.

By the morning of the Rams’ Nov. 30 home game against the Oakland Raiders, Givens, tight end Jared Cook and receivers Tavon Austin, Stedman Bailey and Kenny Britt had decided they were willing to take that risk. They told hardly anyone what they were planning, not even teammates or coaches.

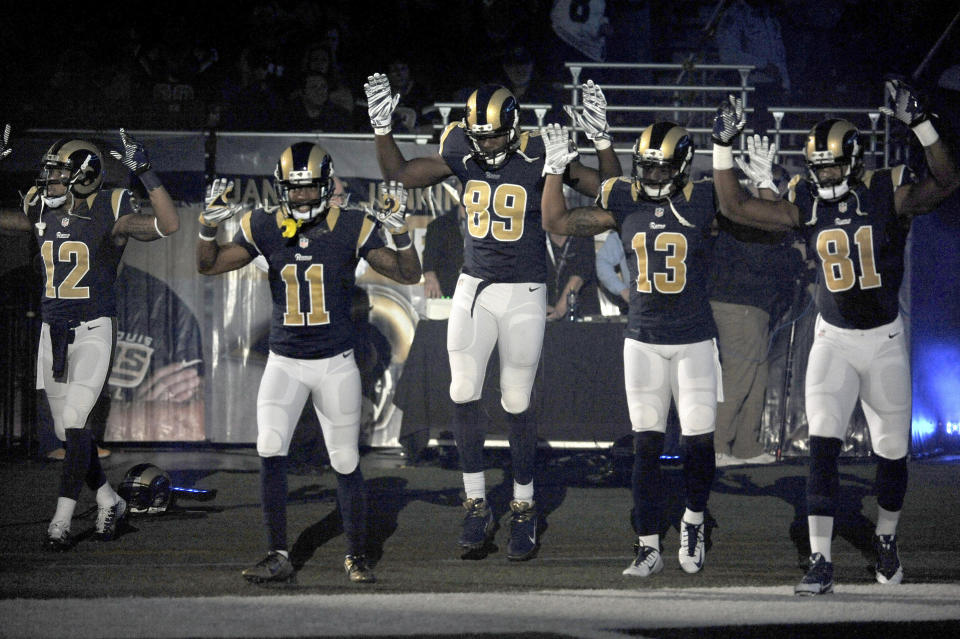

During pregame lineup introductions, Austin and Britt emerged from the Edward Jones Dome tunnel with arms raised as though they were surrendering. Bailey, Cook and Givens then came out and adopted the same “hands up, don’t shoot” pose.

The gesture was a reference to the “hands up, don’t shoot” slogan popularized by Ferguson protesters after some witnesses initially claimed Brown had his arms raised when he was shot. According to a subsequent Department of Justice investigation, those witnesses later recanted their statements or were discredited by physical and forensic evidence.

Inside the Edward Jones Dome, the crowd responded tepidly to the protest. Once the video aired on CBS and spread on social media, the blowback soon grew far worse.

How the ‘hands up, don’t shoot’ gesture blew up

Before the Rams coaches in the press box could steel themselves for the fallout from the Ferguson Five's protest, they first had to figure out what was happening.

“What’s going on? Why are they stopping?” wondered assistant wide receivers coach Kenan Smith when Austin and Britt paused to wait for their teammates in front of the tunnel. Only after Bailey, Cook and Givens also emerged with arms raised did Smith recognize that this was a choreographed protest.

“Oh, OK, that’s going to get some attention,” Smith recalls thinking. “Then it was game on and you kind of forgot about it, but in the back of your mind, you knew that was the only thing that people were going to talk about.”

Down on the Rams sideline, those coaches also were blindsided. Veteran wide receivers coach Ray Sherman recalls experiencing conflicting emotions, from pride that his guys took a stand, to disappointment that he or head coach Jeff Fisher hadn’t received advance warning, to concern that the protest might be perceived as a distraction.

“I remember thinking, ‘I really hope we win this game,’ ” Sherman told Yahoo Sports, “because if we didn’t win the game, everyone was going to say that this disrupted the team, that this caused guys to lose focus.”

The Rams did not lose focus. In fact, if anything, winning for Ferguson became a rallying cry. A franchise slogging its way through a forgettable second-to-last season in St. Louis delivered an out-of-nowhere display of dominance, demolishing the Raiders 52-0.

When Givens jogged off the field after the game, he naively expected the pregame protest to be a secondary story to Trumaine Johnson’s pick-six, Bailey’s 100 receiving yards and Tre Mason’s trio of touchdowns. Only after anxious Rams public relations staffers pulled him and the rest of the Ferguson Five aside and warned them of the forthcoming storm did it dawn on Givens that he underestimated the impact of the “hands up, don’t shoot” pose.

In a postgame interview with reporters, Cook spoke passionately about Brown’s death and his desire for change. He said, “Everything about the situation touched me because it could have happened to any of us. Any of us are not far from the age of Michael Brown and it happened in our community.”

Britt wore Ferguson tributes on both his wrists, “Mike Brown” scrawled on his right and “My Kids Matter” on his left. Like Cook, Britt told reporters he felt a responsibility to show support for the protests against police bias and brutality, adding, “I don't want the people in the community to feel like we turned a blind eye.”

For NFL fans, the protest was polarizing. Some wrote to the Ferguson Five on social media to thank them for their gesture. Others mailed hateful letters to the Rams’ facility or left voicemails threatening to cancel their season tickets.

Conservative media outlets also slammed the Rams players for mixing politics and sports. In a Fox News segment the day after the game, commentator Greta Van Susteren said, “When I watch football, I want to watch football. I don’t want to watch someone’s political agenda shoved down my throat.”

Most venomous was a statement from the St. Louis Police Officers Association. Spokesman Jeff Roorda described the protest as “tasteless, offensive and inflammatory” and demanded the NFL suspend the five players involved. Roorda didn’t stop there, defending the officer who killed Brown as the victim and framing the “hands up, don’t shoot” gesture as a betrayal to the police.

“As the players and their fans sit safely in their dome under the watchful protection of St. Louis’s finest, they take to the turf to call a now-exonerated officer a murderer,” Roorda said. “That is way out of bounds.”

Criticism from fans and rhetoric from Roorda put the Rams in a difficult position. They weren’t about to suspend their players for speaking out, but they didn’t want to alienate a portion of their fan base either.

St. Louis Rams executive Kevin Demoff expressed regret for any “perceived disrespect of law enforcement,” sparking a debate over whether that constituted an apology. The Rams’ PR team organized what Givens described as a “cease and desist type meeting” to help the Ferguson Five craft an explanation for the protest that would minimize the fallout and make the story go away.

The Wednesday after the Raiders game, Cook met with reporters again to “clean up” misconceptions about the message he and his teammates sent. Cook insisted the “hands up” pose was a show of support for peaceful protesters, not a jab at police officers.

“What I remember most was not being able to do what we set out to do,” Givens said. “We had to spend more time correcting what we’d done than speaking up about the issues that were important to us.”

No Colin Kaepernick treatment

It took a few days, but the Rams got their wish. The news cycle at last moved on from the Ferguson Five after they had been nightly fodder for everything from “First Take,” to Fox News to “The Daily Show.”

That Givens and his teammates didn’t achieve the infamy that Kaepernick did two years later is a result of several factors. Their protest lasted just one week and did not involve the national anthem, making it less appealing for an opportunistic politician like Donald Trump to hijack their cause as a way of riling up his base.

Only Cook is expected to play in the NFL this season, but none of the others were exiled like Kaepernick. Britt had more than 1,000 receiving yards for the Rams in 2016 and signed with Cleveland and New England the following year. Austin earned a training camp invite from the 49ers last month before a knee injury dashed his hopes of making the team. Two gunshot wounds to the head prematurely ended Bailey’s NFL career in 2015, while Givens washed out of the league in 2016 after brief stints with the Ravens and Eagles.

“I don’t think the protest was held over any of their heads,” Smith said. “Jared is still thriving in New Orleans. The others were just business decisions. There’s a reason we all say the NFL stands for ‘Not For Long.’ ”

In the six years since the “hands up, don’t shoot” protest, the NBA has long since overtaken the NFL as America’s most socially conscious professional sports league. Last month, NBA players even threatened to detonate their season in a unified protest against racial injustice, an act of disobedience that seems unlikely to be replicated in the NFL anytime soon.

The differences between the team-first NFL and the star-driven NBA stem from their cultures, commissioners and salary structures. NBA players on guaranteed contracts don’t have to worry about their team cutting them if they become a “distraction.” Only the top tier of NFL stars has such job security.

“Some of the lower-level guys may not speak out as often as they would like because they don’t want to be in a position where they lose their jobs,” Sherman said.

Slowly, that’s changing.

In June, amidst protests over the brutal killing of George Floyd, commissioner Roger Goodell declared the NFL was “wrong for not listening to NFL players earlier” regarding the systemic oppression of Black people. Since then, many of the league’s coaches have not just given players the green light to protest but actually led the fight for social justice themselves.

As the NFL season kicks off, Givens expects to see players finding all sorts of creative ways to stand against racism and to promote the Black Lives Matter cause. Those players undoubtedly will not receive universal support, but they’ll also face far fewer obstacles than Givens and his teammates did just six years ago.

“Back in 2014, protests and things like that were still frowned upon,” Givens said. “There wasn’t as much support as what guys get now.

“I’m proud of what we did because we tried to stand up for something. It gets a little overlooked because of the Kaepernick thing, but it’s part of history. It’s exciting to know we were part of the trail.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Lifestyle

Yahoo Lifestyle